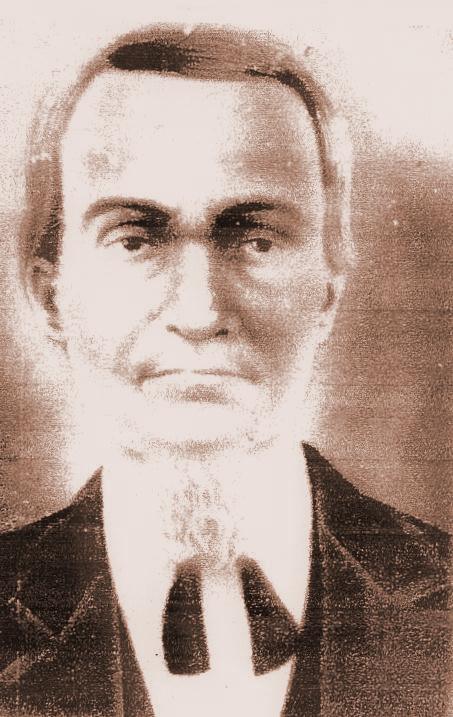

Murrell Askew

1811-1884

Murrell Askew – The Reluctant Baptist

By C. Wayne Kilpatrick

Murrell Askew is virtually unknown outside of Lauderdale County, Alabama. He is not well known, even within the families who descended from him. One might even question how much these families really know about Askew. Much misinformation still circulated about his life. In spite of all of this anonymity and being misunderstood, Askew was a major catalyst in causing the Baptists of North Alabama to restudy the Bible, and to question the creeds of the day. The purpose of this writing is to give documented information on this forgotten “soldier of the cross.”

Murrell was born in Williamson County, Tennessee, not far from Franklin. He was born to Aaron and Elizabeth “Lovey” Askew on March 4, 1811. His father Aaron, was born in North Carolina in 1789. At the age of 22 he moved with his wife to Tennessee. Hosea Holcomb says that Aaron was a “wicked, profane man, but felt a keen conviction for sin . . ." (Hosea Holcomb, History Of The Baptist In Alabama,( Philadelphia: King and Baird, 1840), p.208.) He further states: “In 1816, he removed to Lauderdale [County, Alabama], a profligate deist." (Ibid.) In 1818 he was converted and “forsook some of his evil practices; such as profane swearing, Sabbath breaking, etc.” and he was baptized in the beginning of 1819.

He was ordained to preach in 1826. Just how serious he was as a preacher has been questioned. Percy D. Wright kept a journal and wrote several things about the Askews. His aunt Elizabeth had married Murrell Askew on March 2, 1845. (Marriage Book 5 (1841-1852) Lauderdale County Courthouse, Florence, Alabama.) Young Percy heard many tales about Aaron and Murrell Askew. He wrote: “Askew would preach and say, ‘Do as Askew says, not as Askew does.’" (P.D. Wright’s Handwritten Journal.) He further stated that Askew was a “drunken preacher.” (Ibid.) Young Murrell grew up under these circumstances, whether all of these charges about his father were true or not true.

We do know that young Murrell became religiously inclined early in life. He managed to get a fair education, and used the Bible as a main source of reading. In 1844, we find him subscribing to Tolbert Fanning’s Christian Review. (Tolbert Fanning, Christian Review, Vol. 1, No. 2, p.24.) Murrell has grown up in a very volatile time, when the Baptists in Northwest Alabama were rethinking their theology, and many were becoming members of the Church of Christ. In 1830 the Muscle Shoals Baptist Association passed a “Resolution” against “Campbellites." (B.F. Riley, History of the Baptists Of Alabama, 1895, p.79.) This must have influenced his later thinking upon the Bible.

Murrell tried his hand at farming, but was not very successful. In 1850, Murrell owned a hundred and sixty acres of land, but only had 20 acres as improved or tend-able land. (1850 Agricultural Census, Lauderdale County, Alabama, p.567.) He was listed as a schoolteacher and had a wife and three young daughters. (General U.S. Census of 1850, Lauderdale County, Alabama, Entry Number 814.) Sometime between 1850 and 1854 he began to preach. Mid year, 1854, he established the Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church in Lexington, Alabama. The church officially organized on November 30, 1854 in “a newly built house near Lexington, Lauderdale Co., Ala." (“Organizational Minutes,” Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church, 1854, p.1.) Askew preached on an irregular basis until 1857 when he became their regular minister. He was their minister until 1861. This was the year the Civil War began. During the war, most rural churches completely disbanded. This may explain why Askew was not listed as their minister. A G.W. Garrett served for a few months and left. The church was nearly dormant until 1868, when they re-hired Askew as their regular minister. (Ibid.)

Askew did, however, continue to preach during the Civil War on an irregular basis. The year of 1862 was an especially bad year for Murrell. His father, Aaron, died that year, and his brethren began to rumble about his theology, which they called, “Campbellism.” Askew was preaching: “that the sinner must obey all of the requirements of the gospel”. He stated, “that the sinner could not claim the promise of the pardon of sins save through obedience to the condition." (Wm. Comer, Gospel Advocate, May 11, 1876, Vol. 18, No. 19, p.454.) He tried to get his accusers to discuss the subject with him, and they refused.

Murrell continued to preach as he understood the Bible, but many Baptists searched the Scriptures to disagree with him. Many honest hearts saw the truth and aligned themselves with him. Two such men were William Comer and R.T. Lanier. Both men would subscribe to the Gospel Advocate and share their learning with their neighbors. (Wm. Comer, Gospel Advocate, 1875, p. 1174.) Comer explained his actions to the Advocate: “When I find a person that I think will lay down their prejudice, enough to read and investigate, I get them to read them [the Gospel Advocate and T.W. Brents’ Gospel Plan Of Salvation]. He further speaks of Askew’s reading these publication. Also he mentions that other leading Missionary Baptists were now changing their views on salvation. (Ibid.) Some of the Baptists had now aligned themselves with Churches of Christ. At least the four congregations, over which Askew had to oversight, had dropped the name “Missionary Baptist,” and simply referred to themselves as “churches of Christ,” by 1875. These changes would cause Murrell Askew much trouble.

In 1874 trouble arose from some of his brethren, after some eleven years of peace. He was brought before the Indian Creek Association and charged with preaching “Campbellism” again (the same year he was rehired as regular minister for the Mt. Pleasant Baptist church near Lexington.) He asked the Association to define the doctrine of “Campbellism.” They told him that he was teaching that all sinners had to do was believe and obey the gospel in all of its requirements, and they would be saved. They told him to stop preaching this kind of doctrine. He told them he would stop for twelve months (which would have been until the next Association meeting) if the Association would agree to discuss the doctrine. They refused to do so.

The Association met in September of 1875 at the Union Grove Baptist church, in the present community of North Carolina, in Lauderdale County. The Association refused to let Askew be heard on any subject. Comer said it was because “the church where he held his membership (Mt. Pleasant) sent him as a delegate, and sent her letter under the name of “church of Christ” with no “Missionary Baptist” added to it. (Wm. Comer, Gospel Advocate, May 11, 1876, Vol. 18, No. 19, p.454.) The Association withdrew fellowship from the church, because they retained Askew as their preacher. When they refused to discuss these matters with him, he said that he would “no longer wear the gag, and that he was now at Liberty to clear his conscience by preaching the Gospel as revealed. (Ibid.) The four churches over which Askew had charge did divide and adopt the name, “Church of Christ.” The Union Grove church was one of these churches. It eventually became the North Carolina Church of Christ, which still thrives today (2007) with over two hundred members. Comer said that all four churches “obligated themselves to take the Scriptures and nothing else for their rule of faith and practice, and to ignore all confessions of faith and man made laws, and contend for the apostolic faith and practice." (Wm. Comer, Gospel Advocate, May 11, 1876, Vol. 18, No. 19, p.754.)

Askew and Comer persuaded all of the Baptist churches in the area to come together for a union meeting. This was held at Union Grove in 1876, probably in May or June. It was reported by Jesse Turner Wood of Cedar Plains, Morgan County, Alabama in the Gospel Advocate of August 10, 1876. He said that one preacher from Missouri and one from Tennessee attended this meeting. Wood said that “good feeling prevailed and much zeal was manifested on the part of many who have been heretofore called Baptists." (J.T. Wood, Gospel Advocate, Aug. 10, 1876, Vol. 18, No. 31, p. 378.) Wood further stated:

This country east and west will furnish a repetition of the Kentuckians 40 or 50 years ago. There are a number that have gone too far to retrograde, and that too, the best of talent . . . There are large numbers in this country moving out of Babylon with good and substantial leaders or teachers at their head, so that the day is at hand when doubtless many will say, ‘why am I thus?’ (J.T. Wood, Gospel Advocate, 1876, p.738.)

This upheaval continued among the Baptist ranks for the next four or five years, with Askew leading the way. The Baptists saw the problem so pressing that in their churches they began polarizing, and trying to prevent our brethren from using the same facilities. An example of this was at Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church, which now had “the Gospel Party,” as the reformers were called, and the Regular Baptists meeting in the same building. Askew was preaching for the “Gospel Party.” Eventually the reformers withdrew to the Salem Church building, about four miles away and began worshipping there. Mt. Pleasant began to be called the “Scrouge Out” church. As a footnote to this upheaval at Mt. Pleasant, the Baptists dropped Askew from their records as their minister. (Mt. Pleasant 150th Year Celebration, p.5.) He continued with the newly formed Church of Christ at Salem School house, about four miles south of Lexington on Mill Creek. Askew had helped to start the Salem Baptist Church at this place in 1859. (Mt. Pleasant Record Book, 1859.) It is stated that 15 members of the Mt. Pleasant Baptist Church had been transferred to Salem to start a mission work. This was in William Comer’s neighborhood. R.T. Lanier also lived in that vicinity. These two men became the leaders at Salem, after Askew moved to Woodland Springs, a community on the bend of the Tennessee River, about ten miles west of Florence. R.W. Officer came and preached at Askew’s home, where he had recently formed a church. Officer baptized seven people. (R.W. Officer, Gospel Advocate, 22 (July 1, 1880) 27:423.) From there, he went to Savannah, Tennessee and preached on the street corners, and baptized two and found another from the Baptists to be favorable in starting a New Testament Church. They raised between eight and nine hundred dollars toward building a building. They vowed to build the building, and to be a church. (“Askew to Wm. Comer,” Gospel Advocate, Nov. 4, 1880, p.712.) He crossed the Tennessee-Alabama State Line and headed southward toward home. This road took him through the Shaw community where Poplar Springs Methodist Church was located. He preached seven or eight sermons in the Methodists house of worship and “all the prominent members pulled out of creedism."(Ibid.) Askew said that “the” pastor in charge threatened heavily but shot weakly; he pledged his right arm and his blood if he did not remove all that I had done.(Ibid.) Askew said the Methodist members begged their preacher to debate him, but he refused. The preacher vowed that next Sunday he would “smash” Askew’s teachings. Murrell said that he only exposed “his own ignorance and evil spirit."(Ibid.) The year 1880 had been a very busy year for Murrell.

Undoubtedly, Officer had talked with Murrell Askew about work among the Indians, since Askew was ¼ Choctaw Indian. They had been associated since the 1870’s and had endured similar fates among the Baptists. Askew may have laid the plans to work with Officer among the Indians when Officer visited Murrell in June of 1880. (R.W. Officer, Gospel Advocate, 22 (July 1, 1880) 27:423.) In 1881, Officer sent for Askew to join him in the work in Indian Territory. Askew was skeptical at Officer’s method of mission work, because he did not use a missionary society to aid him in the work. Askew, who had only been severed from Baptist’s Missionary Societies for about six years, still trusted, to some degree, in societies. Askew’s skepticism was revealed in an article that appeared three years after his death, in which he reported as saying:

I confess I had but little confidence in its (mission work) success. Others looked upon it with some suspicion, and we all wondered why Bro. O. did not do like other missionaries over here . . . (“Mission Work,” Octographic Review 1 (Jan. 4, 1887) 1:3.)

Officer had come from the same Baptist background as Askew, but he had completely rejected any kind of society work. He was convinced that unity would be promoted if individual congregations supported the work, instead of societies promoting it. Askew is further quoted as finally realizing the truth in Officer’s method. He stated: “. . . but we are now convinced that we were mistaken, for we find that it does not divide, but has a tendency to bring the churches together in mission-work." (Ibid.)

Askew set up his residence in the Chickasaw Nation; which seems odd, as he was part Choctaw, not Chickasaw. He converted many Chickasaw Indians in the short time he worked there. He began teaching at Burney Institute, an Indian School near Lebanon, Oklahoma. It would make sense that he would teach school, to support his family, as he had been a school teacher back in Alabama. During his first year at Burney, the building partially burned. (B.C. Burney, “Chickasaw Academic Leaflet,” May, 1881, Vol. 1, No. 111, p.121.) For the next two years he taught at Burney Institute, and continued to do mission work. He became ill in the late fall of 1883 and died on January 4, 1884. He was laid to rest on the school grounds, at the institute. This ended the life of a man, who had worked among the Baptists until he studied himself into the New Testament Church. He had worn the Baptist name, but for years, before his leaving, he did not agree with the typical doctrines of the Missionary Baptist Church. His struggles with that organization show him truly to have been a “reluctant Baptist.”

His work and legacy still lives on in Lauderdale County, Alabama, and Savannah, Tennessee in the churches he established. Even T.B. Larimore’s success among some Baptist churches in that area, may partially been due to Askew having blazed the way for him. May many generations profit from this good man’s labors.

-C. Wayne Kilpatrick, Florence, Alabama

![]()

Burney Institute

Oklahoma

Burney Institute

Site In Vicinity South

Established 1854 by Chickasaw

Council, Daugherty Colbert, Chief;

David Burney; Joel Kemp, George D.

James, A.V. Brown, school trustees.

Opened as school for Chickasaw

girls 1859, under supervision of

Cumberland Presby. Bd. Rev. Robert

S. Bell and wife, teachers. Name

changed to Chickasaw Orphan Home

And Manual Labor School, 1887

The land on which the old Indian training school sits is owned by the Chickasaw nation. In 2004, I had the privilege of visiting the location when it was still privately owned by the Robertson family of Ardmore, Oklahoma. I personally spoke with Lila Robertson and her husband on a couple of occasions in the process of seeking the grave of Murrell Askew. The couple were very kind in their explanations of the school, and the property. She remembered growing up in the house, and playing around the building of the old school as a child. However at the time of our phone visits, Mrs. Robertson was saying that as she and her husband were getting older, and unable to take care of the property, they were seriously thinking of deeding it back to the Chickasaw nation. Within the next eight years it became a reality. When visiting the location this year, I was amazed at the transformation. Old weeded and barbed-wire road frontage had been replaced by white picket fences and the entrance had been moved to a better location. What had at one time been farmed land, was transformed to fields that were regularly mowed.

When I arrived everything was locked up tight, and inaccessable. It appeared to not be open to the public. However, while standing there, a white pickup "just happened to" drive up. The young man driving explained that he was the caretaker and proceeded to allow me access into the location. I was free to go and look anywhere I wished, at my own risk of course. I took photos of the old building of the institute, some of which are shown below. I then made my way out to the cemetery which lies about 100 yards slightly southeast of the old homestead. It was located up under some trees. Though it did not look like a perpetually kept cemetery, it was a far cry better than it was when I visited it in 2004. I was so pleasantly pleased with what I saw. So much work has been done to improve the site. The Askew plot is located at the southern end of the cemetery. Murrell Askew's monument is broken and lying face up. I was able to stand it up, clean it a little and even chalk it. (photos below). Here is a list of those buried in the cemetery: http://www.rootsweb.com/~okmarsha/burncem.html

Speaking with the caretaker, he was unaware of any immediate plans to restore the old buildings. It would probably be cost preventive unless someone took it upon themselves to assist the nations financially. If you are interested in helping with this preservation project, you should contact the Chickasaw nation.

![]()

The Campus Of The Burney Institute

Now In The Hands Of The Chickasaw Nation

*see comments at the end of the page

These souls now walk with the Creator.

a part of our memory

We care for our ancestors

now returned to their journey

"Ah ba banilli Aanowa"

Repatriated by the Chickasaw Nation

May 2010

The Grounds of Burney Institute

The Front of the School - Facing East

The East Side Of The School

The House Originally Had A Second Floor

The old school building is condemned and unstable-in much need of repair.

Below are photos from different angles

The Front - Eastern Entrance

The Back Of The Building - Facing West

The house on the left was at one time two stories. The top floor was removed years after the close of the school.

The Southern End of The House and Building

Looking At The School Grounds From The Burney Cemetery From The South

The House At One Time Had A Second Floor

![]()

Directions The Grave Of Murrell Askew

Murrell Askew is buried in the cemetery located on the grounds of the old Burney Institute. It is located about 1 1/2 miles east of Lebanon, Oklahoma. Lebanon is located in the south central region of the state, just north of the Texas border. Take I-35 south of Ardmore to the city of Marietta. Take exit 15, Hwy. 32 east through Marietta. Continue past Marietta on Hwy. 32 for 13 miles to the little town of Lebanon. Travel east of Lebanon on Hwy. 32 for about 1 1/2 miles and look of the old historical marker for the Burney Institute on the right, just before the road makes a hard turn to the left(north). The gate may be locked. However, if you are able to gain access, then go to where the old homestead and school building (both standing in 2012), and face the house. You will be looking west. Turn to your hard left, even a litte further, and across the field about 100 yards away is the Burnette Cemetery. The Askew plot lies in the southern end of the cemetery. GPS Coordinates of the grave of Murrell Askew - 33°58'34.1"N 96°53'14.5" / or D.d. 33.976136, -96.887352

![]()

Cemetery Photos

Burney Cemetery in the distance - photo taken from the house, toward the south

This is how the cemetery looked when I first arrived. Murrell Askew's grave marker is broken and not easily seen from this vantage point.

The Askew section of the cemetery at the south end.

The grave marker of Murrell Askew as I initially found it February 23, 2012

Aaron Askew

Born

May 17, 1867

Died

December 11, 1891

Aaron was the 3rd child of Murrell and Eliza Askew

Jasper Askew

December 17, 1890

Died

December 27, 1890

Grandson of Murrell and Eliza Askew

Cleaned up as good as I could given the circumstances

If you use this or any photo on this page, please ask

How this looks compared to the first time I saw this you would not believe it was the same marker!

Rev. Murrell

Askew

Born

Mar. 14, 1811

Died

Jan. 4, 1884

Gone but not forgotten

Askew's chalked grave can be easily seen in the distance

![]()

Photos Taken February 23, 2012

Webpage updated 09.07.2020

Courtesy of Scott Harp

www.TheRestorationMovement.com

Web editor note: In February, 2012, it was my privilege to visit the grave of Murrell Askew. I was invited to take part in the annual Affirming The Faith Lectureship in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Getting into the area early, I was afforded the opportunity to put about 2000 miles on a rental car in order to locate graves of gospel preachers and church leaders of yesteryear in a wide area. My fourth day I was able to visit the grave of Murrell Askew. His wife, Elizabeth "Eliza" Wright Askew is buried in the Lakeview Cemetery in Marietta, Oklahoma, a few miles south.

Note: Photos on this page are downloadable for free. However, if used in other locations please seek permission. Email Me!

![]()