Six Days In North Prison On Duke Street:

Glasgow's Bridewell For Untried Prisoners

Location of 1847 Imprisonment of Alexander Campbell

Glasgow, Scotland

upper left - Glasgow Cathedral;

upper middle - Duke Street Prison;

Upper Right - Location Of Glasgow University where Campbells Attended

Alexander Campbell spent 10 days in a prison, located just across the street from where he attended Glasgow University nearly 40 years before.

Source: http://www.hiddenglasgow.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=119&start=15

![]()

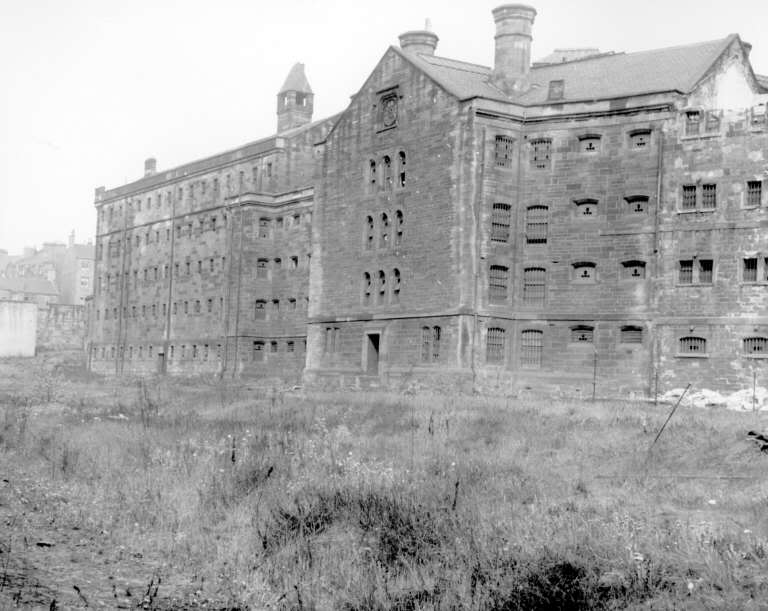

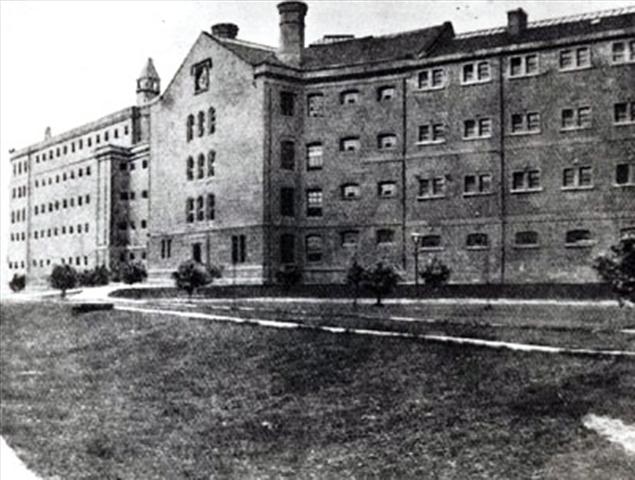

The Glasgow Bridewell moved to Duke Street in 1798. It contained 115 cells originally. In December, 1824 an additional wing was added with 150 cells, making it one of the largest prisons in all of Scotland. Alexander Campbell called it, "a stone cold castle."

Note: A bridewell is a Scottish term for a jail or prison.

![]()

Excerpt From Memoirs Of Alexander Campbell

On the morning of Monday, the 6th of September, [1847] Mr. Campbell, accompanied by a few friends, directed his steps to the cemetery at Glasgow, and, as he says, spent one of the most beautiful and happy forenoons he had enjoyed in Scotland, “in conversing with the living and yet communing with the dead.” Passing over the “Bridge of Sighs” beyond the old cathedral, where the waters of Molindinar Burn dash violently over an artificial cascade into a deep ravine, he reached the city of the dead, where amidst elegant monuments and beautiful shrubbery lay the crumbling memorials of five-and-twenty generations, and where, nearly forty years before, he had occasionally rambled and spent many a moonlight hour in solitary musings. In the afternoon of this day, while he was expecting to continue his lectures in the evening and to complete his course in time to meet his appointments in Ireland, he was presented with a warrant from the sheriff of Lanark to prevent him from leaving Scotland.

Source: http://www.hiddenglasgow.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=119&start=15

This was done at the instance of Rev. James Robertson, who had received the thanks of the “Anti-slavery Society” for placarding and opposing Mr. Campbell, and who, having found his previous measures unavailing to prevent the people from hearing him, and having become still further exasperated by Mr. Campbell’s allusion to him in his letter from Dundee, had based upon the latter a suit for damages, the amount of which he placed at five thousand pounds. Representing that Mr. Campbell was about to leave the country, he had now succeeded in obtaining a warrant in meditatione fugae, rarely used and designed to prevent the escape of debtors. Mr. Campbell’s counsel demurred to the warrant, and the case was heard before one of the sheriffs, who with some distrust decided that it was legal. The case was then appealed to the high sheriff, who was no other than Archibald Alison the historian, who adjudged the warrant legal, but reduced the amount specified in it of five thousand pounds to the comparatively paltry sum of twohundred pounds. Mr. Campbell’s counsel then appealed to the Superior Court of Scotland, to the lord ordinary, who happened then to be Lord Murray.

“Meantime,” says Mr. Campbell in his account of the matter, “there must intervene no less than ten days before the case can be tried before Lord Murray. And now the question with me was, Shall I give security or go to prison? Security was kindly offered me, but that relieved me not as respects my duty to the Lord, his cause and people. I felt myself persecuted for righteousness’ sake, and I could not find in my heart to buy myself off from imprisonment by tendering the required security. I thought it might be of great value to the cause of my Master if I should give myself into the hands of my persecutors, and thus give them an opportunity of showing their love of liberty, of truth and righteousness by the treatment of myself in the relations I sustain to mankind as a Christian and a Christian teacher—an advocate of the apostles’ doctrine in Scotland—in her capital cities; I therefore placed myself in the hands of these superlative philanthropists, the Anti-slavery Society of the whole kingdom. I felt the idea of imprisonment in all its horrors—of being immured in a cell or cold dark dungeon for an indefinite period; I thought of my appointments in Ireland, and of all that might be lost by not fulfilling them; I thought too of the dangers to my health, greatly impaired by one hundred days’ incessant talking. But casting myself on the Lord, I said, to the astonishment of the friends around me, ‘I believe that in all this I am persecuted for the truth’s sake. I stand for the Bible doctrine in faith, in piety and morality, and I am resolved to give no security. I will rather go to prison.’

Source: http://www.hiddenglasgow.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=119&start=15

“Mr. Robertson’s counsel, fearing the consequences, said if I would pledge my word that I would be back from Ireland within the time, he would take my word for it. Thanking the gentleman for his kindness, I said, ‘Sir, I shall still be a prisoner and obliged to return; I cannot consent to return on the warrant issued. I will go to Ireland, sir, with your permission and without promise to return.’ He said he could not grant that. ‘Then,’ said I, ‘your pleasure be done.’ He walked into another room. Mr. Robertson and the sheriff followed him. The sheriff asked Mr. Robertson what he should do. Mr. Robertson told him to inquire of Mr. Jameson, his counsel. Mr. Jameson sent the sheriff to Mr. Robertson for his mandate, refusing to give any. Mr. Robertson said, ‘Take him to jail’— and to jail I went.”

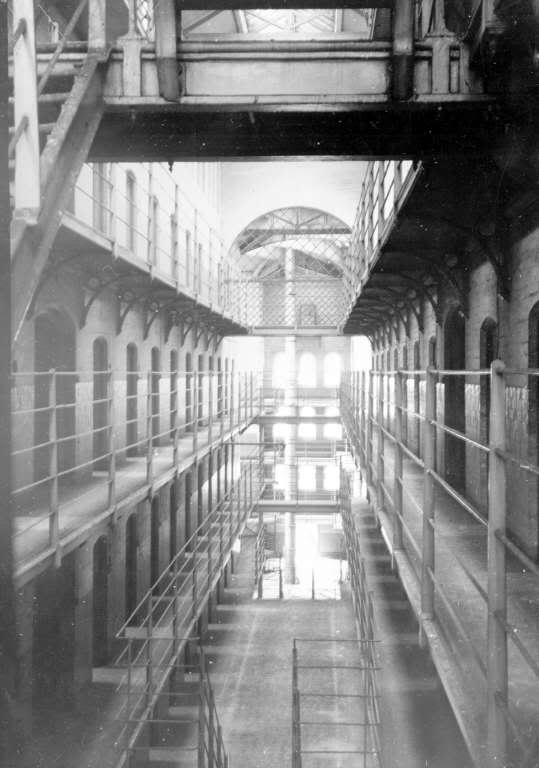

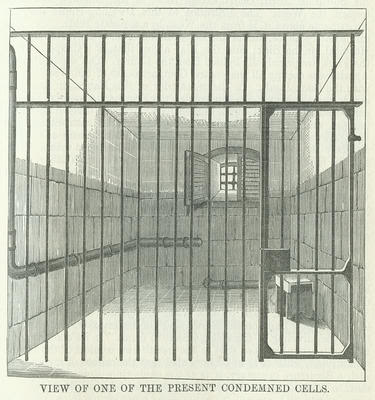

Messrs. Henshall, Paton and Stalker accompanied Mr. Campbell to the prison, which they found to be built of stone. He was confined in a small room, where there was little light and no comforts save a stool and a small table, with a piece of carpet, two feet by four, on the cold stone floor.

The brethren in Glasgow strongly disapproved of Mr. Campbell’s course in positively refusing their offers of security, and subjecting himself, as they thought, unnecessarily to confinement. They urged him to accept their offers of bail, arguing that the object of the law was merely to secure the presence of the defendant. He was a foreigner and about to leave the country, and the object of the court was to secure his presence to answer to the decision of the suit. This would have been equally well attained by giving bail for his appearance, as the law provided. They furthermore urged that they did not think it was the wish of the prosecutor to imprison, but if it was, it was wrong to afford him that gratification when it could have been avoided. Nor did they fail to suggest that much good might be lost by his failure to fill the appointments falling due.

Source: http://www.hiddenglasgow.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=119&start=15

Disposed as Mr. Campbell was ordinarily to weigh with care the counsels of his friends, and often to modify by them his own conclusions, on the present occasion their arguments and entreaties produced no effect. Knowing that he had done nothing to merit such treatment, that he had never been an apologist for American slavery or a defender of man-stealers, as falsely and calumniously represented in the placards, but that on the contrary he had used all his influence and opportunities for the emancipation of slaves, he felt that he was persecuted, if not for his religious views in general, at least certainly because, in opposition to the Scotch Antislavery Society, he maintained that the mere relation of master and servant was not in itself sinful, but was sanctioned by the Bible. Looking back over the whole series of indignities to which he had been subjected, he could not but regard the whole as simply a persecution for the truth’s sake. Such, indeed, had been the character of Mr. Robertson’s proceedings that the more intelligent of his own party denounced the whole affair as a matter of persecution. Thus the editor of the “Christian Record,” published in Jersey, said in regard to it:

“We regret exceedingly the issue of this matter. What ever be Mr. Campbell’s opinions in regard to slavery— and if he entertains the views attributed to him, we hold them in abhorrence— we cannot but regard him as a persecuted man. We know not the nature of the libel with which he is charged, but this we know— that his opponents have been unscrupulous in their language and most unrelenting in their persecution. Following Mr. Campbell from city to city, from town to town, they have hunted him more like a wild beast than a human being, much less a gentleman of education and a minister of the gospel. While we yield to no man in the intensity of our hatred to slavery in all its forms, we question very much if the procedure of the secretary of the ‘Antislavery Society’ in Edinburgh will raise his character in the estimation of the thinking portion of mankind, or at all promote the object of the excellent society with which he is identified. We would strongly recommend him to withdraw his action and throw himself upon the moral sense of the community. It is possible by our imprudence or the exhibition of a persecuting or vindictive spirit to ‘build again the things we are endeavoring to destroy.’ Let us not fail to remember that the ‘wrath of man worketh not the righteousness of God. ‘”

Source: http://www.hiddenglasgow.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=119&start=15

Feeling accordingly that he was persecuted for righteousness’ sake, Mr. Campbell could not for a moment think of evading in any respect the sufferings which his enemies sought to inflict. In the days of his youth, when consecrating himself to the service of God, it had been to him one of the strongest evidences of a divine call that there had been given to him a desire “to suffer hardships and reproach” for the sake of the truth. Of misrepresentations and slanders, indeed, he had already had a full share, and, like Whitefield, he seems to have thought that it was to be his lot to suffer still severer trials.

“My work,” said Whitefield to one of his American coadjutors, “is scarce begun. My trials are yet to come. What is a little scourge of the tongue? What is a thrusting out of the synagogues? The time of temptation will be when we are thrust into an inner prison and feel the iron entering even into our souls. Then, perhaps, even God’s people will be permitted to forsake us for a while, and none but the Lord Jesus to stand by us.”

Mr. Campbell, however, was not destined to realize the latter part of Whitefield’s exultant anticipation. Far from forsaking him in the hour of suffering, the Disciples in Scotland vied with each other in their unceasing efforts to minister to his comfort. The Sisters Paton, Gilmour, Dron and others in Glasgow waited on him daily with everything needful. A Sister Davis, who had heard him preach at Paisley, and had then resolved to emigrate to America and cast in her lot with the Disciples, upon hearing of his imprisonment came at once to Glasgow and was assiduous in her attentions. From various parts of Scotland, indeed, his many friends flocked in to visit him, so that all day long they were coming and going, and he had sometimes as many as eleven in his cell at one time, through the kind indulgence of the jailer, for the law strictly allowed but two persons at a time to visit a prisoner, and that only during two hours of the day. Multitudes of letters likewise poured in upon him from all parts of England expressing the kindliest sympathy. His situation was thus rendered comparatively comfortable, and his chief regret was, that he had caused so much pain and grief to many of his brethren and sisters. Maintaining his accustomed serenity and cheerfulness, he conversed as usual upon the interesting themes of the gospel with his friendly visitors, or occupied his quiet hours in writing. Being without fire, however, and deprived of his usual exercise, he felt a severe cold constantly accumulating in his system, notwithstanding all his prudence and care, so that when, after *ten days, Lord Murray heard the case, declared the warrant illegal and ordered his discharge, he found himself quite unwell.

-Robert Richardson, Excerpt from Memoirs of Alexander Campbell, Vol. 2, pages 557-563

![]()

Directions To The Old Duke Street Prison Location

The Duke Street Prison has long been abandoned and demolished. Tenement housing now exists all around the original prison campus. It is located in the older city area. See photos below. GPS Location: 55°51'38.5"N 4°14'15.7"W / D.d. 55.860695, -4.237695

![]()

Views of the Old Duke Street Prison Before It Was Demolished

Source: http://www.hiddenglasgow.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=119&start=15

Source: http://www.hiddenglasgow.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=119&start=15

Source: http://www.hiddenglasgow.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=119&start=15

![]()

Views of What the Area Of Duke Street Prison Looks Like Today

Sight of location of the old prison from the corner of Wishart and John Knox Streets

(Note: The Glasgow Necropolis is behind the photographer)

View of Prison Wall from High Street

Looking From Prison Wall Toward Glasgow Cathedral

Looking in the direction of where the old Duke Street Prison stood

Your web editor, Scott Harp with his wife Jenny at the only wall still standing of the Old Duke Street Prison

![]()

Photos Taken During Two Visits: November, 2006 & January, 2012

Stock Photos of Prison: Source: http://www.hiddenglasgow.com/forums/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=119&start=15

Courtesy of Scott Harp

www.TheRestorationMovement.com

Special Thanks to Graham McDonald, Scottish preacher who ushered your web editor, Scott Harp, and his wife, Jenny, to Reformation locations around Scotland in November, 2006. Also to Richard Harp, our son, who is a missionary in Scotland with his wife, Mary and our grandson, Gabriel. One day he took me around to visit the old site of the imprisonment of Alexander Campbell in 1847.

*Note: Richardson reports that Alexander Campbell was imprisoned for 10 days. It appears that he reasoned this as Campbell explained to him that if he went into prison it would be ten days before the judge would hear his defense. Saying he was in jail ten days did not account for Campbell's finally succombing to friends offers to pay his bail on the 11th, in his sixth day. Also, his schedule, and events known by other researchers, put the days in prison at 6 days and 5 nights. He was arrested on Monday the 6th, as Richardson correctly includes. Finally, he was released on the 11th. He made attempts to preach the following day. Eva Jean Wrather's series: A. Campbell, Adventurer In Freedom, Vol. 3, page 169, says he was released after six days. This would put the release on Saturday, the 11th.

![]()