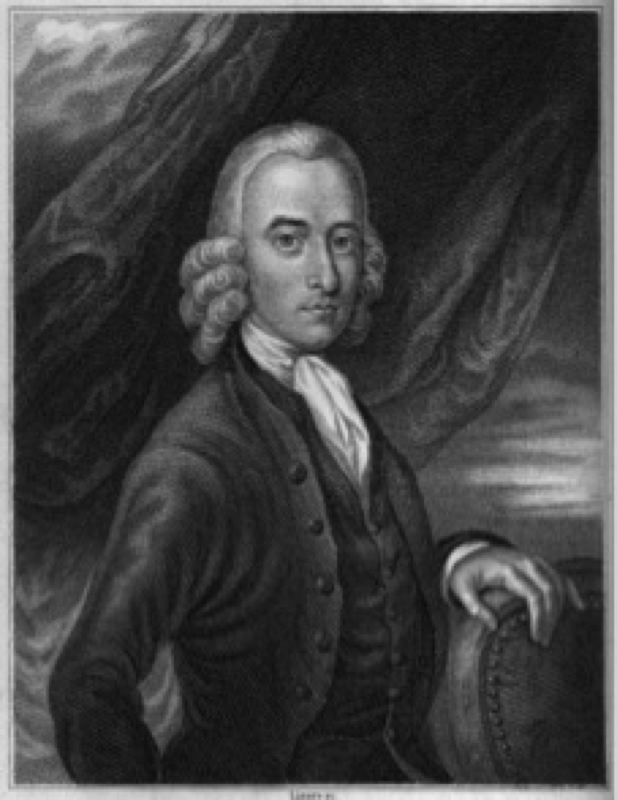

Robert Sandeman

1718-1771

![]()

The Life and Times of Robert Sandeman

[The following material is taken from Br. McMillon's book "Restoration Roots," and is used by kind permission of the author. A few items have been added by the Editor of this history.]

BORN IN PERTH on April 29th, 1718, Robert Sandeman was the second of David and Margaret Sandeman's 12 children. David, a linen merchant and magistrate in Perth, sent Robert to the University of Edinburgh to prepare for the ministry of the Church of Scotland. Robert was a diligent student and developed proficiency in mathematics, Greek, and other languages. But Robert was uncertain about his career plans.

Shortly after entering the university (around 1734), Robert met John Glas and some of his Christian associates. Within a few weeks Robert was converted to Glas' persuasion. He also took part in the church where Glas was an elder. After completing two terms at the university, Robert returned to Perth in 1735 to serve an apprenticeship in the weaving business. He was now convinced that he was not suited for a career in the Church of Scotland or medicine.

He married John Glas' daughter, Katherine, in 1737, and later set up a weaving business in partnership with his younger brother, William, in 1740. After four years, Robert left the business to devote more time to the church. His share of the income from the business provided him with a comfortable living for the remainder of his life. Robert was not the only Sandeman to marry one of Glas' daughters. In 1756, Robert's youngest brother, Thomas, married Annie Glas. For the first seven years of his marriage, Robert worked in the linen business and became increasingly involved with the tiny church in Edinburgh. During those years Glas' affection for Robert grew.

When Robert was 26, his father-in-law urged him to accept appointment as an elder. Sandeman, described by a contemporary as "naturally diffident, modest, and keenly conscious of his youth and inexperience", was hesitant to accept the solemn responsibility of the office offered him. Eventually, however, he consented and was "set apart to the elder's office in 1744.” Within a few months he left the linen business in his brother's hands and devoted full attention to his duties as an elder for the church at Perth. For the next 16 years Sandeman preached at Perth, Dundee, and finally at Edinburgh, during which time his brother, William, was converted.

While serving in his home-town of Perth, Robert had the painful duty of reproving his father, who was rather indifferent to spiritual responsibilities. In a previous letter, dated March 16th, 1733, his father had requested restoration to the fellowship, confessing "his rash and sinful deserting of the profession of faith.” On that occasion he was received back into fellowship. In Robert's letter to his father in 1745 he stated his deep concern. William Jones, of London, possessed the original letter, which he published in September 1835. It is a remarkable letter by any standard, not only because of the deep, earnest spirituality it reveals, but also because, whilst displaying a warm affection and respect for his father, as a father, Sandeman makes it abundantly clear that he fears for his father's spiritual welfare and urges him to repent. He recalled boyhood impressions of his father's devotion at Tealing and Dundee and expressed disappointment at his father's latest and longest lapse. Calling his father to repentance, Robert pleaded: "Be not ashamed to confess your sins freely ... let not the world, reproaching you for changeableness, hinder you from making another change yet, and returning to your duty.” Sadly, on this second occasion there is no record of his repenting. In the letter Robert laid a portion of the responsibility for his father's laxity on the fact that his mother had never fully agreed with, nor supported, her husband's beliefs.

The decade 1745-55 was uneventful as John Glas and Robert and William Sande man worked with the struggling independent congregations in Central Scotland. During these years the Sandemans, along with Glas and his son George, became the chief advocates of the faith in the midst of a hostile religious environment in Scotland. Although other ministers worked diligently for the success of the movement, without Glas and the Sandeman families wide acceptance would never have come.

Controversy with James Hervey

During the height of the great debate in England between the Calvinists and the Evangelicals in 1755, a book appeared entitled "Dialogues between Theron and Aspasio.” It was written by James Hervey (1714-1758), a well-respected Calvinist minister from Northamptonshire. Hervey's discussion of imputed righteousness attracted the attention of many in England who hailed the brilliance of his work. John Wesley attacked it in his tract "A Preservative Against Unsettled Notions in Religion.” Robert Sandeman saw Hervey's work as an opportunity to teach what the Bible had to say on the matter. Sandeman wrote a response which catapulted the struggling independent churches of Christ into public recognition and respectability.1

Hervey's work explained the depravity (total evil) of human nature. In the preface to "Theron and Aspasio" he stated; "But the grand article, that makes the principal figure, is the imputed righteousness of our divine Lord . . ." His purpose was also to explain the worship and articles of faith of the Church of England. After two years of correspondence with Hervey, Sandeman responded in 1757 with "Letters on Theron and Aspasio," which underwent four Scottish editions and one American edition. The impact of Sandeman's work was felt strongly in England. Two of his readers, Samuel Pike and John Barnard, of London, began corresponding with him. That correspondence, together with the publicity given to his ideas, led to the establishment of a new congregation. Though the death of John Hervey in 1758 ended the correspondence, the thinking of Robert Sandeman was by then well known. Not only was the impact of Sandeman's thought felt throughout the British Isles; it also spread to America where religious leaders read and discussed his work. Thus the ground was prepared for the planting of new congregations in England, Wales, and America. For the next several years Sandeman replied to numerous letters from English Independents and Americans who were impressed with his fresh understanding of New Testament Christianity.

Influence in England

Samuel Pike (1717-1773) was an Independent minister of a congregation at Three Cranes meeting house, Thames Street, London. He, and members of his assembly, were avid readers of Robert Sandeman's material. Pike became so interested in Sandeman's interpretation of faith that he wrote Sandeman on January 17th, 1758. Within a year Pike and several of his members began to sympathise with Sandeman's positions and to share Sandeman's letters with John Barnard, another Independent minister in London. The latter began writing to Sandeman in 1759 and soon agreed with him on Biblical matters.2

Due to Sandeman's impatience with Pike, their correspondence cooled. Nevertheless, Pike adopted several new practices, including weekly observance of the Lord's Supper. This decision aroused suspicion among his fellow-ministers who refused him a speaking position on the annual lectureship held by English religious Independents at Piner's Hall in 1759. Throughout 1760, some dissidents in his own congregation tried to depose him, but his supporters were always in the majority and they retained him.

Since John Barnard was a more likely prospect for starting a congregation in London, Sandeman concentrated his efforts on him rather than Pike. Barnard was not a highly educated man; but he had met George Glas, the son of John, in London while the younger Glas was preparing for one of his sea voyages, and was impressed.

Enthusiastic Interest from London

On July 9, 1759, Barnard wrote to Sandeman describing his inner turmoil and the impact of the "Letters on Theron and Aspasio" upon him. "I thought of burning them, yet dared not; for I plainly saw, though against my wish, that if your account was, as I began to fear, according to God's testimony, I was wrong ... " Barnard asked if elders were necessary for a properly organised church and how many persons were needed to form a church. Elated at the possibility of establishing a church in London, Sandeman replied: "From a summary view of the New Testament it appears that a presbytery or plurality of Elders is necessary to complete the form and order of every church"3 He then encouraged Barnard to begin a congregation: "If you can find a dozen of the poorest and least esteemed in London who appear to love the truth and are frankly disposed to join you in obeying it, much better to set out with them, under the care of the chief shepherd, than entangle yourself with others, however noted for piety or wealth, to the grief and vexation of your heart in the issue. If you should need or desire any assistance from us in the business of forming yourselves into the apostolic order, I have ground to assure you that the churches in this country would be willing, at their own expense, to send you some of their presbyters to assist you for some weeks."4

Sandeman's letter inspired Barnard. On August 9th, 1759, he was prepared to join with the few sympathisers from his own congregation and take the first step toward forming a congregation after the apostolic order in London. Barnard agreed substantially with Sandeman on matters of doctrine, although some points needed further discussion. One can sense the mixture of determination and nervousness among Barnard's small group. Barnard wrote: "I am ready, small as the number is, to run all hazards with them in obeying the truth and cleaving to the Lord with purpose of heart, as soon as providence shall open a door for our union." It seemed to Sandeman there was a hesitation on the part of the London people to set themselves up, formally, as an Independent congregation. He grew impatient with them and after an exchange of letters, Sandeman turned to George Hitchens, with whom he had been corresponding since December 1759, as a better hope for the establishment of a congregation in London.

London Church Finally Established

However, by mid-summer of 1760 Barnard again appeared ready to establish a New Testament congregation and informed Sandeman that he had rented Glover's Hall, where he would be meeting with eight other members. Thus the Sandemanian church in London came to be established in early autumn of 1760. Barnard explained to Sandeman how these early services would be conducted.

"The manner we propose is this: In the first place it seems proper for me to declare the reason of my hope, and the profession of my subjection to Christ, with freedom and brevity, as in his sight. This will be followed by each of them doing the like, and shewing they are not ashamed of Christ nor of his words before men. If in doing this we appear to each other to be of one heart and of one soul ... we shall, by standing up and giving each other the right hand of fellowship, signify our satisfaction, and rejoicing for the consolation, join in prayer to him who hath said, I will dwell in them and walk in them.'"5

Sandeman was delighted at this positive move by Barnard. The little congregation began immediately to study the order of the New Testament church, seeking first to appoint elders. Within six months the members decided they could not celebrate the Lord's Supper without a plurality of elders. Barnard wrote to Sandeman to explain that the time formerly devoted to the Lord's Supper was being spent in prayer for elders. He was also glad to report that their numbers had risen to 14, with other interested parties attending.

Initial Disappointing Visit to London Crowned with Joy

Sandeman, accompanied by his brother William, and John Handayside, an elder from Wooler, left Scotland for London in April 1761. Upon arrival in London, the delegation from Scotland found Barnard and the Glover Hall congregation reluctant to unite with them. Consequently, Sandeman turned to George Hitchens, with whom he had corresponded, and quickly formed a congregation which began meeting at Butcher's Hall.

Throughout 1761, Barnard corresponded with John Handayside concerning some questions that remained in his mind. Handayside answered these questions to Barnard's satisfaction. Barnard then wrote to Sandeman on March 18th, 1762, apologising for the delay in making a decision to unite with them. He wrote: "I know of nothing so desirable in this world as that I and my friends may now at last be one with you and yours.” Upon receipt of this letter, Sandeman departed immediately for London.

By mid-April Barnard and his congregation united with the existing London congregation, led by Hitchens. They all moved to Glover's Hall, which was more spacious. Barnard and Hitchens were appointed elders. About three years later, on December 22nd, 1765, Samuel Pike and several of his followers joined the church in Glover's Hall. The congregation, now greatly enlarged, moved first to Bull-mouth Street, then, in 1788, to Paul's Alley, Barbican, London. By the tum of the century the church had grown strong and was well known. In 1808 a contemporary described their essential doctrines as the weekly observance of the Lord's Supper, weekly collection, kiss of charity, plurality of elders, and the practise of discipline.

The conversion of Samuel Pike and his followers in 1765 greatly strengthened the church and added prestige to its name. John Barnard wrote in June 1766 to Sandeman, then in America, that Pike was an elder and the membership of the church had reached 106. Two years later Barnard again wrote to Sandeman rejoicing that the membership had grown to 149, besides other groups meeting in the country, and that a meeting place was being sought in the west end of London for a second congregation since they had elders enough to serve both churches.

Spread of the church in England

The church in London became the centre of former evangelistic efforts in England. Within a few years a dozen congregations had been established in other parts of England, some of them being supplied with elders, preachers, and members from London. By the late 1700's the Restoration Movement had three avenues of endeavour: Glas leading the Scottish Restoration; Barnard, Hitchens, and Pike leading the English Restoration; and Sandeman initiating the Restoration in America.

Soon after the beginning of the congregation in London, a Restoration Movement emerged in the counties of Nottingham, Yorkshire, Lancaster, Westmorland, and Cumberland. They merged with the Scottish churches and the London church, after meeting Glas and Sandeman. Some of these churches were originally affiliated with Bernard Ingham, and the members were known popularly as "Inghamites.” After reading the works of Glas and Sandeman, Ingham appointed William Batty and James Allen, two of his ministers, to visit the churches in Scotland. Both men returned to England ardent supporters of Glas' teachings. Even so, the merger was not without its difficulties. In the October 1761 conference of the Inghamites strong feelings were expressed about how they would make the change from their own Methodist society arrangement to congregational church government.

James Allen and his wife, along with seven men and five women, left the Inghamites and formed a restoration church at Gayle in Lancaster on June 30th, 1762, another nine persons were added the following day. Two years later new congregations were formed at Kirkby-Lonsdale with 16 members; at Newby with 24 members; Kirkby-Stephen with 30 members. A letter of June 1768 revealed a congregation in Liverpool with 17 members, and another at Colne with 37 members and three elders.

A congregation was established in Nottingham through the efforts of Samuel Newham, an acquaintance of Barnard, who introduced him to Sandeman's writings. Newham wrote to Sandeman in November 1759; as did Richard Sanson and T. Bowler, in 1760, about the restoration of New Testament Christianity. In October 1767 Barnard visited the church in Nottingham. In April 1768 there were 18 members, including elders.

Congregations were soon established in Norfolk and Essex. By 1766 the congregation in Banham had 37 members with two elders. John Boosey, one of the elders at Banham, is described by Barnard as "partaking in the wants of the poorest peasant, attending them in their sickness with refreshments, medicines, and all with such an abundant cheerfulness, that I think him the happiest man I know in the world.”6

A small church was formed at Weathersfield, Essex, probably in 1767. It had six members by 1768 and was enjoying regular visits from brethren at Banham and London. In June 1766 Barnard reported to William Sandeman that a Mr. Hart of Bristol, along with 16 others, had formed a congregation. In May 1768 Barnard, and an elder named Davies, visited Trowbridge and established a congregation of six members, which included John Morley who had moved from London, where he had been an active member. It was also reported that three disciples had formed a church in Salisbury, Wiltshire.

On into Wales

The spread of the movement to Wales was due mostly to the 1765 Welsh translation of the writings of Robert Sandeman. The first known Welsh convert was a Methodist minister named John Popkin who had studied the works of Glas and Sandeman. He even translated and printed several of them in Welsh. In 1766 Barnard and Pike formed a church in Wales and the news was promptly sent to Glas by Popkin. The following year Barnard, along with an elder and a member, returned to Wales where they were enthusiastically received by Popkin and the few other members. For the next three weeks nightly meetings were held in addition to the usual love-feast (fellowship meal) on Sunday afternoons. When the brethren returned to London they left a congregation of 14 members, with John Popkin and W. Powell as elders. The church met in Swansea.

Popkin enjoyed the assistance of the popular Welsh preacher David Jones of Cardigan. Together they established congregations at Carmarthen, Llangadock, and Llangyfelach, as well as other towns in South Wales where small groups met. In 1768 Barnard reported to Sandeman that the church in Wales was doing well, although it was not spreading rapidly.

About 1795 the Welsh Restoration movement experienced a revival in North Wales due to the work of John Richard Jones of Criccieth. Later, the Criccieth church was to form strong bonds with the Restoration Movement of the Campbells in America. Lloyd George, Prime Minister from 1916-22, was associated with the Criccieth church.

Move to America

While the work was reaping fruits in Britain, Robert Sandeman received an invitation to preach in the New England states in America, where his writings were already widely circulated and held in high regard. Consequently, he, and James Cargill, an elder from Dunkeld, sailed from Scotland on August 30th, 1764, and arrived in Boston on October 18th. Sandeman stayed there for a week, visiting people and preaching three times in The Green Dragon tavern to a small group of interested persons. His preaching caused no small stir amongst the communities of New England, and many of the Congregational ministers regarded him as a threat to their own cause.

Ezra Stiles, a leading Congregational minister, and later President of Yale University, heard with interest of Sandeman's arrival. He was familiar with the teachings of the Sandemanians, and was convinced that their teachings of the Bible were sound. He also developed a personal acquaintance with Robert Sandeman, whom he met, and discussed with, on a number of occasions. It was to Stiles that many anguished ministers wrote. John Barret Hubbard wrote that Sandeman "is a very artful man, and if I mistake not, the ablest instrument the Father of Error has ever permitted to send amongst us.” However, Stiles was eminently fair in his judgement and replied to another concerned minister, "I believe he has sown a seed in America which will up and grow, though I have no apprehension of any great ill effect.”

Sandemanian Missionaries Multiply

David Michelson arrived from Scotland to join forces with the preachers already in New England - Sandeman, Cargill, and Olifant. They travelled extensively preaching the word of God with varied success. Eventually they arrived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on April 20th, 1765. At the conclusion of two weeks' preaching they were blessed with fruits for their labours. In the words of Mitchelson, "the first Church of Christ in North America was constituted May 4th, 1765, at Portsmouth, New Hampshire.” There was a membership of 20. Several of the Sandemanian churches survived the American Revolution (1775- 83) and lasted well into the 1800's. Alexander Campbell had contact with two of them. In all likelihood Sandeman and his fellow Scottish missionaries would have succeeded in establishing the church of Christ permanently on American soil, except for two factors:

1. The unstable King George III was on the throne. The American Revolutionary War was about to break out. Sandeman and his followers believed they, and everyone else, should obey the king in London, and this made their preaching unpopular in many circles. As patriotic fever in preRevolutionary America rose to a high pitch Sandeman's teachings were regarded with disdain, a feeling reflected in legal enactments against the Sandemanians in Connecticut. This feeling also had a negative effect on the growth of the churches, for who would want to belong to a group that was so politically unpopular!

2. Sandeman's untimely death in 1771 at Danbury, Connecticut. While churches continued to be established after his death, Robert Sandeman was the moving force behind the endeavour.

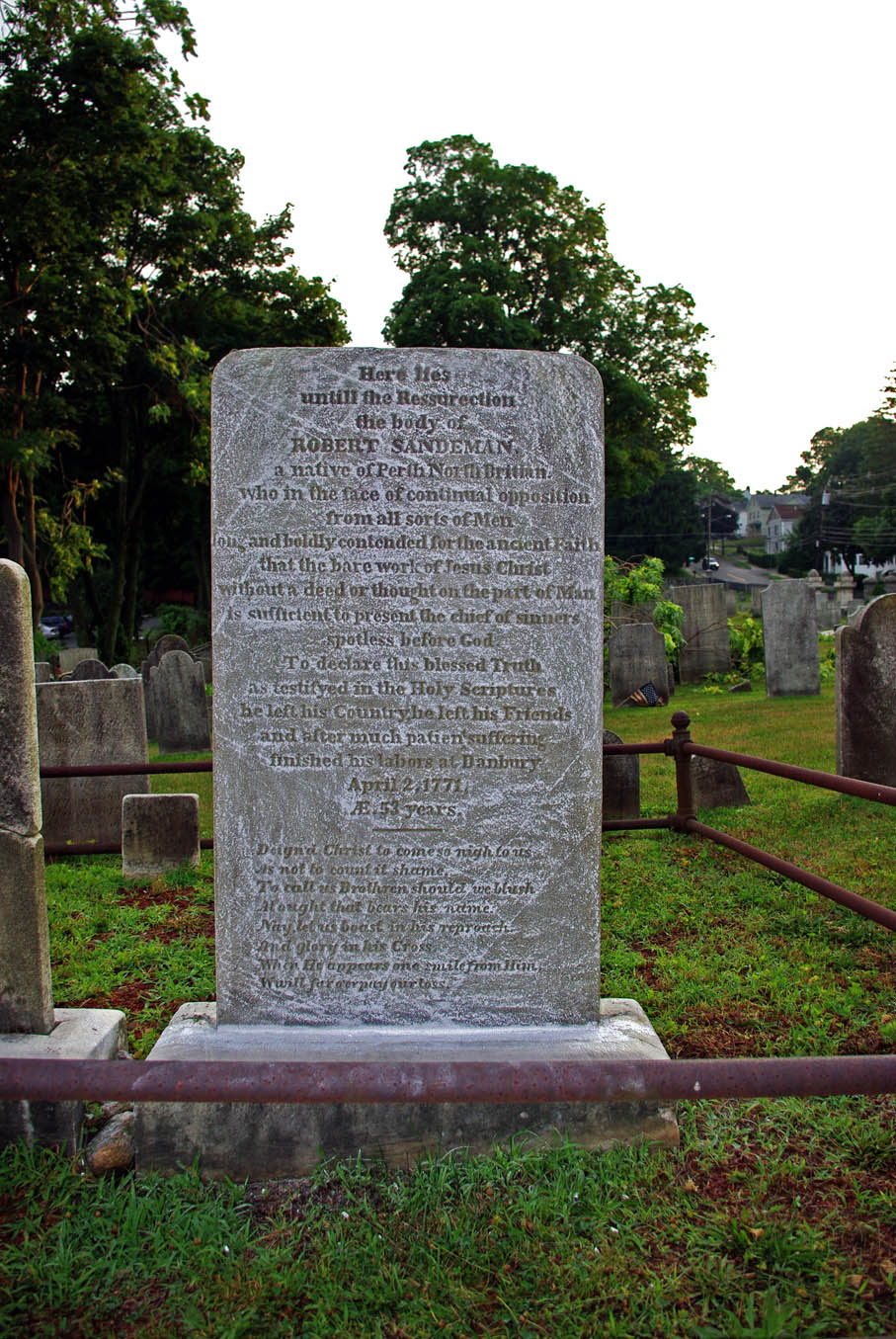

The following epitaph was engraved on his tombstone, which still stands at the front of the old cemetery in the heart of Danbury:

Here lies

until the resurrection

the Body of

ROBERT SANDEMAN,

A Native of Perth, North Britain

Who in the face of Continual Opposition

From all Sorts of Men

Long and boldly contended

for the Ancient Faith;

That the bare Work of Jesus Christ

Without a Deed, or Thought on the Part of Man,

Is sufficient to present

The chief of Sinners

Spotless before GOD:

To declare this blessed Truth

As testified in the Holy Scriptures,

He left his Country - he left his Friends,

And after much patient sufferings

Finished his Labours

AT DANBURY,

2d April 1771

Aged 53 years

How Others saw Robert Sandeman

How any of us are remembered after death is often subjective, and Robert Sandeman is no exception. A month before his death in America, James Duncan of Glasgow, one of Robert's contemporaries, penned the following testimony to the character of Robert Sandeman.

"While connected with Mr. Sandeman in church fellowship, I have often freely acknowledged that if ever I knew a man by whom I was in danger of saying with the Corinthians, I am of such a one,' Robert Sandeman was that man. Yet I can, with a good conscience, say it was not because he was a fine writer or preacher; but my regard for him sprung from the fervent unaffected regard he daily witnessed to the Gospel, displaying nothing of the master, but exemplifying the brother in Christ, destitute of all those little politics which are essentially necessary to form the character of what is falsely termed 'a good disciplinarian.'"7

Alexander Campbell, in his "Christian Baptist" Vol. 3, April 3rd, 1826, drew distinctions between the spirit of the Haldanes and the Sandemanians, when he wrote: "Concerning Sandeman and Haldane, how they can be associated under one species is to me a matter of surprise. The former is a paedobaptist, the latter a Baptist; the former as keen, as sharp, as censorious, as acrimonious as Juvenal; the latter as mild, as charitable, as condescending as any man this age has produced. As authors I know them well. The one is like the mountain storm that roars among the cliffs; the other like the balmy zephyrs that breathe upon the banks of violets."

Doctrinal Teachings of Robert Sandeman

Although similarities existed between the thinking of Robert Sandeman and his father-in-law, John Glas, several differences were evident. The primary concern of Glas was the non-binding nature of the Scottish national covenants, whereas Sandeman's greatest concern was the nature of faith.

Nature of the Church

Robert Sandeman believed the true church would never become large, because size would corrupt it. He observed that Christ spoke of his followers as constituting a "little flock.” He believed the "flock" would follow the strict teachings of Christ and exclude all popular religious practices. In their interpretation and pursuit of these laudable aims, stem discipline was a feature in their assemblies. Sometimes this very austerity proved to be too great a burden for some. Sandeman explained to Ezra Stiles that persons could not be received into the church without the unanimous consent of every member in the local congregation. He also explained that they rigidly adhered to Matt. 18:15-17. "Upon any difference, they practised Christ's rule immediately till it was bro't before the church and settled and made up in the week; for there could be no communion (which they celebrate every Lord's Day) if a single member had aught againt (sic) a brother.”8

Church Offices

It was Sandeman's view that a church was not complete in its formation until elders had been ordained. They often abstained from the Lord's Supper until they had elders; for this reason elders were usually appointed soon after a new congregation began meeting.

Elders were selected by the entire church, and then ordained by the laying on of hands of an existing eldership. Sandeman explained to Stiles that the elders usually followed secular employment as did the apostles, but "if any Elder had a peculiar taste for books and was much addicted to them and employed his time wholly in study, there would be no difficulty but that the Brethren would support him."9

Sandeman also explained that there should be no senior presbyter or moderator, and that the titles of bishop, elder, or presbyter applied equally to every elder. In accordance with New Testament example there could be no teaching elder separate from the ruling elders. All elders should perform both of these duties as well as baptising and administering the Lord's Supper.

The two primary duties of the deacons were to take care of the weekly distribution of the Lord's Supper, and the care of the poor among the membership. The deacons did such a thorough job of caring for their own poor members that outside assistance for them was not required.

Church and State

Sandeman resisted all forms of church-state connections. He acknowledged the authority of the state, but taught submission to the higher powers "which be ordained of God.” On the question of military service, Sandeman taught that a Christian could bear arms in his country's defence but not on account of religion. He regarded obedience to the civil authorities as essential in the practise of true Christianity, yet he stressed the separation of church and state.

Justification and Faith

Faith, for Sandeman, had two meanings. First, in salvation man merely accepts the redeeming work of God rather than performing any work of his own. Second, faith is an attitude or way of life, rather than a mental activity. In "Letters on Theron and Aspasio" he discussed the dynamic power of the gospel as it grows in a person through faith. "When once a man believes a testimony, he becomes possessed of a truth; and that truth may be said to be his faith."10 He illustrated his idea by saying that upon hearing an alarm bell a person will respond with a feeling of fear, yet it is the bell that has done the work. The feeling of fear is merely a response based on an understanding of the meaning of the bell. Sandeman was careful, however, not to make faith meritorious. He insisted that justification comes from what is believed, and not from belief itself; and faith is not true faith until it causes a person to love and obey the will of God.

The Lord's Supper

The Lord's Supper was observed weekly in congregations having elders. Other congregations, who did not have elders, either omitted it or partook only when elders from another congregation were present. The belief was not that elders had to administer the Lord's Supper, but that without elders a group of Christians was not a truly constituted church. The observance of the communion came around 2 p.m., following the morning worship and noon meal known as The Love Feast. The holy kiss was often practised at the Love Feast. As the meal was about to begin, one of the elders would kiss the cheek of the person on his right and so on until the kiss made the circuit around the table. Sandeman, however, observed that "these customs were not observed as divine institutions but rather as exemplary imitations of the primitive Christians.”11 They agreed that there was nothing in themselves, or in any other person, to commend them to God as they broke the bread. Every communicant had to be at peace with all of his brethren before he could observe the Lord's Supper.

Worship Service

Worship was held on Sunday, with brief devotional meetings being held on Tuesday and Friday evenings at 6 p.m. In Scotland the congregations had their own meeting houses. In England they met in rented halls or homes of brethren. In America they first met in homes, and later in meeting houses.

A typical Sunday service would last from 9 A. M. to around 6 p.m. From 9 A. M. to 10 A. M. the public were excluded. When the doors were opened to the general public at 10 A. M. there would be singing, which was always "a capella" and consisted mainly of Scottish hymns composed by Glas, Sandeman, and other talented members. Much time was devoted to prayers and lengthy readings from the Old and New Testament. One of the elders would preach for an hour. This part of the service would end at noon, when the church would assemble at a member's house for the Love Feast, a regular meal at which aspects of religion were discussed and new songs were learned. Only members were allowed to the Love Feast. At 2 p.m. both church members and the public would engage in singing, prayers, and more scripture readings. An elder would bring another hour-long sermon. Just before 4 p.m. the general public would be dismissed, the church would stay in the building and the doors would be shut. The contribution would then take place and every male member gave a short word of exhortation. This latter activity was known as the Nursery of their Ministers, as here were exhibited each person's abilities and aptness to teach. This weekly activity which occupied, virtually, the whole day contrasts dramatically with our present-day worship services which are so much shorter.

Other Distinguishing Features

Names - Sandeman, Glas, and other Restoration leaders referred to themselves as members of the church of Christ, but they did not regard the designation as being a specific name for the church.

Creeds - Sandeman opposed religious creeds. He insisted they were responsible for destroying the purity of Christian doctrine. As Glas before him, he was adamant on relying solely on scriptural authority for all practices and beliefs in the church.

Religious Titles - Preachers and elders declined to use "Reverend" as a title. They deemed it a designation for God alone. Sandeman gave his reasons for refusing the title when he wrote: "The most common preacher in the poorest dissenting congregation still affects to be called "Reverend"; from the same principle which leads the first clergyman in Europe to the title of His Holiness.”12 Sande man also refused to wear clerical clothing because he believed that all Christians were brothers and none should enjoy a position of pre-eminence over the others.

Conclusion

Modem churches of Christ in the British Isles owe a debt to thoughtful men like Glas and Sandeman. They did not shrink from questioning the popular religious views of their day, many of which were immersed in blatant hypocrisy.

Despised by many, suffering for the cause of the Lamb, we quietly honour their diligent search to walk in the old paths.

Endnotes

1 James Hervey, "The Works of James Hervey" (4 vols; II. p.vii.); Newcastle; M. Angus and Son. 1806.

2 Primary sources for material: "Letters in Correspondence by Robert Sandeman, John Glas, and their Contemporaries", Daniel Macintosh (ed.), Dundee: Hill and Alexander, 1851. (The only known copy is in Dr M 'Millon's library). "Supplementary Volume of Letters and other Documents by John Glas, Robert Sandeman and Contemporaries between 1740 and 1780", Perth: Morrison and Duncan, 1865.

3 "Robert Sandeman to John Barnard, July 19, 1759", in "Supplementary Volume of Letters" by S. Morison, p. 21.

4 Ibid., p. 23.

5 Ibid., p. 51.

6 Ibid., p. 69.

7 Testimony of James Duncan, Glasgow, Scotland; March 1771 ; from "Millennial Harbinger" 1835; pp. 280ff.

8 Stiles, Memoirs of Robert Sandeman," p. 29.

9 Ibid., p.30.

10 Sandeman, "Theron and Aspasio", II., p. 37.

11 Stiles, "Memoirs of Robert Sandeman", p. 29.

12 Sandeman, "Theron and Aspasio", I., p. 208

-Lynn McMillan, As it appeared in, "Historic Survey of Churches of Christ In The British Isles," Joe Nisbet, General Editor, pages 34-45

![]()

Directions To The Grave of Robert Sandeman

In Danbury, take I-84 to Exit 4. Take Lake Ave. toward town. Turn right on West St. Turn right on New Street. Turn left on Wooster. The cemetery will be on the right. The Sandeman grave is immediately behind the Danbury Health Department on the east end.

GPS Location

41.390074,-73.448823

View Larger Map

![]()

Sandeman is buried behind the building you see in the distance. It is the old Danbury Health Department Building

Looking up at the Sandeman plot from behind the old Health Department Building

Here lies

until the Ressurection

the body of

Robert Sandeman

a native of Perth North Britain

who in the face of continual opposition

from all sorts of Men

long and boldly contended for the ancient Faith

that the bare work of Jesus Christ

without a deed or thought on the part of Man

is sufficient to present the chief of sinners

spotless before God

To declare this blessed Truth

as testifyed in the Holy Scriptures

he left his Country, he left his Friends

and after much patient suffering

finished his labors at Danbury

April 2, 1771

AE, 53 years,

___________

Design of Christ to come so nigh to us

as not to count it shame

To call us brethren should we blush

at ought that bears his name.

Nay let us boast in his reproach

And glory in his Cross,

When he appears, one smile from him

Will far o'erpay our loss

![]()

Photos Taken July 20, 2012

by C. Wayne Kilpatrick

Site Built on 10.21.2012

Courtesy of Scott Harp

www.TheRestorationMovement.com

Special thanks to C. Wayne Kilpatrick for taking the photos that appear on this site. Also special thanks to Joe Nisbet, Scotish minister of the gospel. It was my dear privilege to visit in his home in 2006 while visiting in Scotland for the first time. He and his wife live in Aberdeen, Scotland. He gave me permission to use any of the information in the book he released on the history of churches of Christ in Great Britain.

![]()