Autobiography Of Thomas Withers Caskey

by T.W. Caskey

Written Two Months Before His Death

It is my purpose to give a brief record of my ministerial life from 1840 to 1895 in three parts-the first from 1840 to 1855; the second, from 1855 to 1875; and the third, from 1875 to 1895. The first, embracing fifteen years, was one of struggle and trial to keep soul and body from dissolving their connection; the second, embracing twenty years, was one of success and triumphs; the third has been considerably mixed up. The first period was the beginning, the second was the middle, and the third is the ending. I will strive to give a fair account of each.

I took to myself a wife before I reached the legal age of manhood. She was a poor orphan girl, with a cultivated mind and a pure heart—a graduate of a first-class college. I was looked upon as a fast young man, bidding fair to come to a bad end. I must confess that that opinion was well founded. I was uneducated, undisciplined, headstrong, self-willed, and of a passionate temperament. I had been free from parental restraints and home influence from the age of sixteen, at which time I left the quiet farm life for a life in a county town, and became an apprentice boy to learn the trade of a blacksmith. I served for three years, working from daylight till dark during the summer months, and till nine o'clock at night in the winter. If we worked later than nine, we received twelve and a half cents per hour. We often worked till eleven when pressed with work, every night in the week, and then spent an hour on the street in all sorts of mischief that the minds of boys could conjure up.

I finished my term of service at the age of nineteen. I received my board and clothes, and was to have received a full set of tools for carrying on my trade, but these I did not get. I packed up my expensive wardrobe in a sack, stuck a stick through the string tied around the middle, and traveled footback from Tennessee to Mississippi, and set up in life for myself. I overseed for a time, and could have made a fortune, as the wages were high and the payments certain; but the slaveowners did not feed and clothe as I thought was right, and wanted their slaves worked too hard. Wild and bad as I was, I still had a conscientious conviction as to what was right, just and humane. I quit the business, refusing a thousand dollars a year with not a cent of expense, and went back to my trade.

As heretofore stated, in 1839 I got a Methodist wife, and, as not stated, the same year I got Methodist religion. The wife was a grand success; the religion, a grand failure. But I got it, as all others do who are run through the proselyting machine of their own inventing—that is, by believing that my sins were pardoned. Faith in this proposition, and not faith in Christ, produces that transition of feeling which is called "getting religion," and this feeling is taken as proof of pardon. Well, I was just a great theological and psychological fool, as all the others who make this absurd blunder. The very feelings obtained by believing that we are pardoned, and that can be obtained in no other way, are taken as infallible proof of the truth of the proposition by which the feelings were begotten. One or the other of the things is bound to be true. Either a person gets this feeling by believing that he is pardoned, or unpardoned he gets shoutingly happy by believing that he is condemned. The latter would be insanity run mad. To take the happy feeling as proof of that which created it is no better. This would be to put the cart before the horse, to raise the stream above its fountainhead, to make the creature greater than the Creator. Such is orthodoxy, but I am indulging in philosophizing on feeling instead of recording my experience.

I came through at a camp meeting, and manifested my feelings in the usual manner of that time by shouting long and loud, and throwing my arms around all who came within my reach without regard to age, sex, or previous condition, color excepted. My brother-in-law was a local preacher, and it did not take him and the circuit rider and presiding elders long to find out that I possessed three qualifications for a preacher for those days and times—scriptural ignorance, intemperate zeal, some degree of impudence, and a good pair of lungs—four instead of three. I was called on to pray in public, speak at our love feasts, and assist in leading the class at our class meetings. The discharge of these duties suggested to them that I was the sort of stuff out of which preachers are made, and insisted that I should be put through their preacher-making machine, ground out, cast into their mold, labeled, licensed, and sent out on a circuit.

This led me to examine our doctrine and discipline—a thing I had not thought of before. I took up the "Discipline" and imagined myself a Methodist preacher. Doctrinally, I found questions innumerable which I could not answer. Turning to the Book of books, I found no answer there. In theory I could not understand how a man could be justified by one thing, and when it came to practice, it took four things. In theory it was by faith only; in practice it was by repenting, believing, loving, and praying. I did not understand it then, nor do I now; nor do they, or anyone else. Not to specialize farther, I found our government to be an ecclesiastical despotism without scriptural authority, and un-American. When my examination closed by comparing the two books, I threw the "Discipline" overboard.

Having weighed the creed in the balances and found it wanting, if I abandoned Methodism, whither was I to turn, and where was I to go? I could not remain with them, and the creeds of others were, if possible, worse. Wife said to me: "Why not examine the Scriptures for yourself? We are commanded to search the Scriptures, to prove all things, and to hold fast that which is good. Our 'Discipline' says that whatever cannot be proven therefrom, or is not clearly deducible or inferable from them, is not binding on us." She had a small Cruden's Concordance. This I took and collated all the Scriptures said on the subject of faith with these questions in my mind: (1) What is it? (2) How do we get it? (3) What is its design? (4) What is its effect? These all being answered by the Scriptures, I passed to repentance with the same questions in my mind, and settled them to my own satisfaction at least, and at that time I was laboring to satisfy my wife and myself only.

I next examined the order in which they were to be obeyed. This being settled, I passed to the third subject—that of baptism—with the following questions: (1) Who are scriptural subjects of baptism? (2) What is the scriptural mode, as we then called it? (3) Who may baptize? (4) What is its design, or why should we be baptized? I reached the conclusion on all these, from which I have not swerved a hair's breadth up to the present time. On spiritual influence I had not thought, and nothing knew, except the popular theory of abstract influence, superadded power, or direct impact to enable the sinner to exercise saving faith. This subject I did not examine till some years after I began to preach.

In my investigation with regard to the order in which these commands were to be obeyed I reached the conclusion that the Scriptures clearly taught that faith was first, repentance second, and baptism third. The theory of all pedobaptist parties was that baptism was first, repentance second, and faith third. Some difficulties here presented themselves to my mind. How, I asked myself, can a man repent without faith? I thought then, and still think, that it is an impossibility, unless the laws that govern the mental and emotional nature of man are annihilated, together with the law of God in revelation, as well as in the nature of man. . . .

The creation of this dogma created another thing not bargained for. It created the necessity for transposing the divine order, and necessity knows no law. They were compelled to bring repentance this side of faith. They could not place it the other side, unless they taught the saved to be sorry that they were pardoned. This, however, would not be more absurd or hurtful than the doctrine itself. Having already shown the conflict between their theory and practice, I need not pursue this thought any further. Their theory says justified by faith only, their practice says by four things—repenting, believing, loving, and praying; and then they have doubts about it after doing three more things than their theory demands.

I now resume the line of thought on which I was touching. Having reached my conclusions on these things, I presented some of my difficulties to my brother-in-law. He had a small library; I had none. Among his books were Clarke's "Commentary," Wesley's "Notes and Doctrinal Tracts," and one volume of Henry on "The Acts of the Apostles." These I carefully read on the mode (so called) of baptism. Instead of being convinced by the strength of their arguments that they were right, I was convinced by their weakness that they were wrong. . . .

Well, I was about as deep in the mud as they were in the mire. Instead of wasting my time pouring over the pages of these writers, worrying my mind and distressing my heart, had there been someone there to baptize me, I could have settled the matter in half an hour, as I afterward did. Was it to do over again, I would say to my wife: "Let us go down to the creek; you baptize me, and I will baptize you." All Christians have a right to baptize. My wife was a Christian, and inherited the right, as all Christians do. It is a birthright. It never was an official act. I have debated this subject many times, and I have yet to meet the man who would debate it the second time. Other issues I have debated three or four times with the same man.

When I developed my views to my brother-in-law, he said: "That is full-grown Campbellism." For the first time this word fell on my ears. I had never heard of this ism before. Said I: "What is that?" He replied: "It is baptized infidelity." I said that I did not know that infidels baptized at all. He then gave me the history of it as far as he had learned it. I found out afterward that he knew no more about it than I did, and those from whom he got it knew as little as either of us. He had never seen or heard one of those who were thus stigmatized, nor had his preaching brethren who were his informants ever heard one of them. I said to him: "If what I have stated to you is what they preach, I would go a long distance to hear one of them, and I did. I did not then know that any man living believed what I then believed.

A few days after this, two of what they called "Campbellite" preachers, traveling on horseback through that part of the state, stopped at a neighbor's house to get their dinner and their horses fed. This neighbor had a brother who was a member of a small church called "Campbellites," "New Lights," "Schismatics," "Heretics," "Baptized Infidels," etc. This I learned afterward. The village at which this small squad had organized was some thirty-five miles from the place where I had set up my blacksmith shop. My neighbor, Captain Darden, had learned something of these people through his brother. I had been there but a year, and knew nothing of this or any other church bearing these names. Captain Darden, learning that they were preachers of his brother's sort, requested them to stay and preach at his house that night, and to this they agreed. He then sent a Negro boy with the announcement through the settlement. His house was large, but the curiosity was larger. The house was full to overflowing, not even standing room left. Heads filled the windows, while the bodies to which they were fastened were outside. Old Brother John Mulkey, from Kentucky, preached an hour and a half, followed by Brother Allen Kendrick with half an hour. Brother Mulkey was in his eighty-sixth year; Brother Kendrick was, I suppose, about thirty, perhaps not more than twenty-five, and boyish-looking except in height. An invitation was given. Captain Darden, his wife, and three or four others who had tried for years to get religion at the mourners' bench, went forward and made the confession required. I arose and asked them to preach at my house the next night, which they did. The house was crowded, as the night before. It was impossible for me to get where they stood. Brother Kendrick preached, followed by Brother Mulkey. They went over the ground which had claimed my undivided and critical investigation for months previous. When the invitation was given, I arose and said: “I do believe with all my heart that Jesus is the Christ, and demand baptism at your hands!' Others did the same, to the number of twelve. The next morning we were baptized. My wife was not in condition to be baptized, but was baptized some months afterward by Brother Darden.

At this time we knew nothing but faith, repentance, and baptism. They told us that it was our duty to meet on every first day of the week to study the Scriptures, to sing and pray, to exhort one another to love and good works, and to honor the Savior's death and resurrection, keeping the day in memory of his resurrection, and partaking of the loaf and cup in memory of his death. They advised us to meet at our houses in the afternoon, as this would not interfere with our going to the other churches in the forenoon, and this for a time we did.

Here is where these preachers made a great mistake, and one which I made for years after I began to preach—a mistake which has been repeated by hundreds of preachers, and is yet repeated by some. The cause is seriously retarded by both. Had these brethren remained, they could have organized a church of perhaps two hundred members, and could have taught and trained them in the work of the Lord, but they had an appointment ahead of them and must go on. The church in that vicinity numbered over two hundred, made up of mixed material. Many could not tell when they were pardoned, others did not believe they were pardoned at all, and others had no religion enjoyment either in the preaching or other religious services. They were simply holding on for fear of dying and going down to ruin. Some had apostatized, having lost their faith in their pardon. At least two-thirds of this church could have been "taught the way of the Lord more perfectly," and made to rejoice in the full assurance of faith and the hope of eternal life. They could not have been hurt by the change, and in this life they would have been filled with joy and peace. All gloomy doubts and misty fears would have vanished as darkness before the rising sun, and they would have died in hope of reaching the better land.

I had no idea at that time of leaving my church. On the following Sunday I took my accustomed seat among the saints—if not saints in light, it was among the saints in darkness. The circuit rider did not preach, but spent an hour in a tirade of abuse and misrepresentaton, bitter invectives and denunciations against the preachers and what they preached, and against all those who believed as they did. He called on my brother-in-law to offer prayer, and the prayer was in keeping with the harangue that had preceded it. When he arose from his knees, I arose to my feet. He commanded me to be seated and be silent, raised his hands, and dismissed the audience. I requested them to resume their seats, which they did, the preacher included. I will not repeat what I said, but, to use a cant phrase, I did a big job of skinning. From that time on for about six months we had a lively time every Sunday; for as we had two local preachers, we had preaching every Sunday. They could not turn me out, and I would not get out. I was the Ishmael in the church; every man's hand was against me, and my hand was against him. My wife's relations ignored us socially; and finally I told them that if they would give me a letter indorsing my religious character, I would withdraw from them. They wished to know what I wanted with a letter. I replied: "To silence the tongue of slander. You dare not slander me while I am one of you; but as soon as I sever the connection, you will say that I was always a hypocrite." They gave me the letter, and we parted.

The first Sunday after the preaching brethren left us we met at the house of Captain Darden, this being the most central and largest one belonging to any of the little band; and here began my preaching life. We did not call it preaching then, but it was preaching, or I have never preached yet. I read an appropriate portion of the word and commented on it after singing and prayer. I did this because I was the only one who could or would do so. We then broke the loaf, sang a hymn, and went out. In a short time some of our less prejudiced neighbors requested us to meet in a large schoolhouse near by. This we did, and soon our house was full every Sunday evening. Brother Darden soon mustered up courage enough to offer prayer and deliver a word of exhortation. This state of things ran for about two years, during which I made no effort to proselyte anyone.

The community was not wanting in wealth, and contained quite a number of intelligent and well-educated people with whom my wife had associated before we were married. When we were invited out to dine or take tea after our marriage, as we frequently were, I soon found out that the conversation ran on subjects that I knew no more about than a goat did of geometry. I was like the boy the calf ran over—I had nothing to say. They talked of philosophy, poetry, science, and art. Their conversation was addressed to my better half. I found myself dwindled down to the position of junior partner in the matrimonial firm, and a silent partner at that. This stung my pride. When we had a dining, where the guests were more of a mixture, we would form two parties on the principle that "birds of a feather flock together." Those of us who had studied and practiced horse-ology, poker-ology, and all the other games of card-ology, showed off our knowledge to each other, while the other party showed off their knowledge of the ologies contained in books. They took no interest in ours, and we took none in theirs. I chafed under this state of affairs, and I soon determined that I would neither play second fiddle to my wife nor dance at the barefooted reel when it came round. I devotedly loved my wife, greatly admired her knowledge, and was very proud of her; but still like a caged eagle, I beat my wings against the bars of ignorance in which I was caged and resolved to break them. I had received but fifteen months' schooling, extending from the age of six years to between fifteen and sixteen. The last six months I went to school I worked an acre of cotton of mornings, evenings, and Saturdays to pay my tuition and get me some Sunday clothing, and walked four miles barefooted over rocks to do this.

With me, to resolve was to do. My wife had some books, I borrowed some, and some I bought. I worked in my shop in the summer from daylight till dark; and for six months, including the winter and part of the fall and spring, from daylight till nine o'clock at night. When my day's work was over, I would go to my house, eat my supper, turn a chair down against what was called the "jam" in the old-fashioned fireplace (chimneys made of sticks and clay), placed a pillow on the back of the chair, lie down on the floor with my head resting on the pillow, and then by the light of a pine knot in the fireplace study for two hours. My work during the day being purely mechanical to a great extent, and therefore requiring but little thought, I would thoroughly digest during the day my two hours' reading of the night before. I studied history, ancient and modern, sacred and profane, logic and rhetoric, and dabbled some in the ologies. I studied English grammar, my wife helping me over the hard places.

After I went to evangelizing, I bought a book and tried my head at Latin grammar. It was my habit to read on horseback, and in this way I read thousands of pages. So I waded into my Latin grammar, got lost in Big Black Swamp, missed my dinner, traveled ten miles out of my way, which gave me a ride of fifty miles to fill my appointment, got there just as the audience was gathering, and got no supper till after preaching. If there is any sense in Latin, I failed to find it, and was so disgusted that I threw my book into the first creek I crossed the next morning, and thus bade adieu to dead languages. I speak but one, and that was taught me by my black mammie, who was from the coast of Guinea. She had forgotten her native tongue, except to count to ten. This, too, I learned from her, and I have found it useful in my debating life. In replying to Greek and Hebrew criticism from pedant preachers who could not read and translate a single verse in either, I would offset them by counting ten in Guinea, thus impressing the audience with the fact that they knew as much of one as of the other; and so we would make a dead fall of it, and I would be bothered no more with that which neither they, nor I, nor the audience knew anything about. These studies were kept up for about two years while I continued at my trade-studying the Scriptures and preaching as I learned. Of course I expected no pay, and in this I was not disappointed.

Near the close of 1842 I followed the wife of my boyhood days to her last resting place in a lonely grove amidst the sighing pines. Standing by her grave, I made a solemn vow that so long as I could keep soul and body from parting company I would devote my life to preaching the gospel of God's anointed Son. That vow I have secretly kept, till now I can preach no more. These are the saddest words I have ever written, or ever expect to write. The hand of earthly fortune has been held out to me, earth-born fame was not beyond my reach, and military power was within my grasp. These temptations were strong; but, thank God, they moved me not. I sold my shop and the tools of my trade, and turned away from that to a higher and holier work. Other hands would now my bellows blow, other hands would make my anvil ring and light up the darkness of the night with showers of sparks from the heated iron; but the memory of these, I felt, would cling to me through life. Long as it has been since, and many and varied as have been the scenes through which I have passed, the clanging of the anvil, as 'tis wafted on the soft breezes of the night, has a fascination for me yet. I quit hammering iron into the shape I wanted it with an iron hammer faced with steel, and went to heating and hammering the souls of men with the fire and hammer of God's word (Jer. 23: 29), but found out by sad experience that hot iron yielded to the blows of the hammer more readily and could be worked into the proper shape much easier than the cold souls of men.

I started out as an evangelist with the promise of $250 a year from a country church some sixty miles from where I had been living. I think their idea was that if the Lord would keep me humble, they would keep me poor. How well the Lord succeeded, I know not; that they succeeded, I do know. Churches were then, "like angels' visits, few and far between—thirty, sixty, and a hundred miles apart If you made inquiry for a Christian church, you would never find it. I went where I pleased, stayed as long as I pleased, and preached as I pleased. I traveled and preached three years before I read a line from any of our own books and papers—not because I could not, but because I would not. I had been badly fooled by great men, which was their fault; but if I permitted great men among us to fool me the second time, the fault would be mine. I said just what the Bible said, and nothing more. I determined to examine all subjects for myself, unbiased and uninfluenced by what others said. In after years I studied the subject of church organization and government.

Originality of thought was a leading element of my mental organization, and the course which I pursued cultivated it. To this I am indebted for all that I am, or will ever be. Occasionally a little of the old leaven would get into my sermon, when some old elder of a church who was free born would call my attention to it; and as I was teachable, that would be the last of it. On one question I differed from the elders and members of the church that sent me out, and also from their preacher, the venerable William Clark, of Jackson, Miss. They wanted me to be ordained by the imposition of hands, but I refused. We discussed the question for several hours. I alleged that I had been preaching for two years. If without authority, then I had been sinning all these years; if with authority, then it must be from a higher source than any or all churches. I claimed a divine right to do any and all things 'that any other Christian could do, male or female, bond or free; that it was a birthright; that the administration of baptism was not an official act; that Paul baptized, not as an apostle, but as a Christian, citing in proof his own language to the church at Corinth. Some of these Corinthians got it into their sapient heads that baptism was more valid when administered by Paul, others by Apollos, and others still by Peter. Paul set his apostolic foot down on all such tomfoolery, and held them quiet till he could get common sense enough into their heads to enable them to understand that all that was needed to help a man to obey this command was a little common sense and physical strength enough to perform the act "decently and in order." Paul inherited the right when he was raised out of the water, and could have baptized others before he changed his clothes.

They made no effort to meet these facts, but said: "Suppose we refuse to license you to preach unless you are ordained by the imposition of hands?" I replied: "I suppose I will do as I have been doing for the past two years—go ahead and preach. I do not suppose that the imposition of your hands, or any other hands, will put any knowledge into my head, or purity into my heart, or money into my pocket; and with me a ceremony that does none of these things has no meaning and is of no use." Without entering on the reason why it was ever done? I pass on. They then asked me what I desired to do. I said: "I am going among strangers, and I want an endorsement of my Christian character, and a statement that you have faith in me that I will preach what you believe. Should I differ from you on any vital subject connected with the scheme of redemption, my self-respect will cause me to sever my connection with the brotherhood as an organization, though still united with them in heart." I have always had but little respect for a preacher who sails under false colors. It smacks too much of the wolf in sheep's clothing.

During the four years following, I traveled far and wide, preaching day and night, making the mistake of not staying long enough in one place and of sending appointments in advance. I baptized hundreds where there was no church, and added hundreds to weak churches scattered over the state (Mississippi). Fortunately or unfortunately, I was drawn into a debate by a church at Oakland, Miss., with a talented Methodist preacher who was an experienced debater. I was but a clerical three year-old calf that had grazed alone on dry grass. I was satisfied that I got badly butted off the track; but our people were satisfied, and so were theirs. The debate was conducted pleasantly; and if no good was done, no harm resulted. Ten years afterward, in passing through Memphis, I found my old opponent in charge of a church in that city. I called to see him, and said to him: "I am convinced that ten years ago you got me under. Since that time I flatter myself that I have acquired some debating sense, having conducted some twenty debates in these ten years. I now desire that we try again." He laughingly replied: "I most respectfully decline. I am content with the laurels won ten years ago, and am not inclined to have them wilted by the same hands that twined them around my brow." His name was Singleton J. Henderson. . . .

At the end of four years I married my present wife, near Gainesville. Ala. She was a widow and the mother of two little boys, age twelve and ten years. She owned a Negro woman, which her father had given to her when the girl was six years old. This woman was the mother of a boy and girl about the same age as my wife's children. I divided my time from 1845 up to 1849 between Alabama and Mississippi, organizing some four churches at Gainesville and in the surrounding community, which numbered from fifty to one hundred fifty members each. I traveled on horseback between Gainesville and Jackson, Miss., a distance of two hundred fifty miles, preaching at night in the county sites along the road, swimming creeks to meet my appointments, baptizing and going on to my next appointment without changing my clothes. I never baptized in my shirt sleeves, nor out of my boots or shoes, and I could not carry a change of clothes.

My trips covered about one month each. Often on reaching home I could spend only two days, and never more than a week. My compensation was $500, out of which I had to pay traveling expenses. My readers will wonder how I supported two women and four children on such a meager salary. I answer: I did not support them at all. My better two-thirds supported herself and the children, aided by her faithful servant, whom she had raised from her sixth year, and who was more of a companion than a slave. We lived on chickens and eggs, milk and butter. Her garden, dairy, poultry yard, and pigpen gave us an abundance. We could have fared sumptuously every day and Sunday too, had it not been for the edict of that universal tyrant, and more than universal fool, public opinion, which decreed that none but Negroes and poor white trash, as the Negroes called poor people before the war, should sell chickens, eggs, or butter. We, being neither Negroes nor poor white trash—God knows we were poor enough, but not trash—could sell none of these things. If I had had as much sense then as I have now, I would have sent a hired, trusty Negro man to Aberdeen on his own hook to sell them as his own. I could have supported two families such as ours, and thus dodged the iron scepter of this relentless tyrant. One year my wife raised five hundred chickens, and of course had eggs by the bushel. We fed the Negro children on them, and gave away the surplus to our neighbors who either could not or would not raise them. Our two weeks' fall basket meeting caused many of their heads to be wrung off, and helped us to dispose of them.

During the four years I preached in that portion of the state, aided by other preachers, the home church, Palo Alto, grew from twenty-six to three hundred fifty, and no "poor white trash" in it. The church was worth not less than $1,000,000. Within an area of three hundred miles we built up ten other churches, embracing from thirty to two hundred members. My salary, as I have already stated, was $500. It is due to the home church to say that they would have paid me more and sustained me among them had they not entangled themselves in a cooperative work without the knowledge to run the machinery. The conventions were composed of delegates from the churches, some of which were located in the black lands where wealth abounded, others in the sandy lands where poverty flourished. To the prairie farmer a dollar looked as big as a dime, but to the piney-woods farmer it looked as big as a cart wheel. As a matter of course, the piney woods were in the majority and fixed the amount of pay. I was offered $1,500 to preach for the church in Jackson or Port Gibson, with permission to hold meetings for destitute churches, for two months of each year, which would increase my salary to $1,800. I offered to remain and evangelize in that large field (Palo Alto) for $1,000, but was voted down.

My children were needing schooling, and I was barely making ends meet. I had baptized two-thirds of those who tabled the resolution offered by the home church delegates to give me the $1,000. Their ultimatum was $600. You may imagine the agony of soul which it caused me. I had baptized more than one thousand in that field of labor. The most successful years of all my preaching life, so far as additions are concerned, had been spent in that field. I resigned in sorrow and disgust, accepted the call from the church at Jackson, and never regretted it. That church was liberal, faithful, and true for six years, up to the time of the war. One year after I left, that large and wealthy church (Palo Alto) withdrew from and broke up the cooperation. Churches were going down as rapidly as they had been built up. They wrote to me to come and hold a protracted meeting. I went and preached for them ten days and nights, and added thirty by confession and baptism. They offered me $3,000 to resign at Jackson, become their "pastor," and hold meetings for destitute churches. I declined their liberal offer.

This closes the first chapter of my preaching life. The trials and struggles for bread and meat were ended forever.

1855-1875

I became pastor of the church in Jackson. Miss. January 1, 1855. I served that church up to 1861, preaching for it three Sundays in each month and one Sunday for a congregation in a wealthy community in Yazoo County, some thirty-five miles from Jackson. The church at Jackson paid me $1,000 a year, and the other church, which I built up, $500. They allowed me two months in which to hold protracted meetings for destitute churches and at favorable points where there were no churches. During these years I increased the number of members in Brandon, and built up a church of sixty members at Hebron, five miles from Brandon in a wealthy farming community. There were three churches represented in that community—Baptist, Methodist, and Disciples—neither of them being able to build a house of worship. Those not members of any church would not aid any one of the parties to build for itself alone. They said: "We want preaching every Sunday, but each of you can give us only one. Unite your means and build a union church, and we will make the balance up. At the same time we will build a female college which will reflect credit on the neighborhood, and we can then educate our daughters and small boys at home." This met the approbation of all concerned. I, as high priest of Jackson Royal Arch No. 6 laid the cornerstone of each, and the buildings went up, and yet stand, and have proved a blessing to all parties.

The buildings completed, we appointed a union meeting, to be represented by a preacher from each religious body. We met and preached alternately for ten days and nights. To each preacher was then assigned a Sunday and the week following. Should he desire to protract, the preacher whose Sunday and week followed gave him his time, and the courtesy was reciprocated. Each organized a church and added to the number of its members. There was not a discordant note heard during all the years that I remained in that part of the state. Some one of our preachers occupied the time allotted to us. We were careful not to tread on each other's theological corns. As the rooster said to the horses when shut up in the stable with them, "Gentlemen, let us be careful not to tread on each other's toes," so we were more careful than we would have been had the building belonged to any one exclusively. I most heartily commend this plan to all country and village bodies of professed Christians.

During the months allowed me for holding protracted meetings I made an average of $300 a year, which raised my yearly salary to $1,800. Some of my Negro children whom I had raised had become producers, and relieved me of some of the burden of supporting so many non-producers. Most of them had grown up in the yard with my own children. My wife often nursed them at her own breast, while her Negro woman, of whom I spoke in the preceding chapter, often nursed our own children. In all my relation to slavery I bought only two Negroes. I was compelled by circumstances to part one Negro woman from her husband. His owner would not sell him, nor would I sell her. She remained unmarried two years, and grieved so much that it excited our deepest compassion. She said she would never marry, if she had to separate again. I told her that it should not occur. She married again, and again I changed my locality. I owned a Negro man really worth more than her husband. His owner, knowing the status of affairs, made me pay $400 difference between them. Her husband died during the war. My nephew, for whom I was guardian, owned the wife of a Negro man that the owner was compelled to sell. He came to me, and the two, husband and wife, cried me into buying him. The reward I got for that act of kindness was that in less than a year he availed himself of the emancipation proclamation and left for parts unknown, so that I saw him no more.

My faithful servant had died at the age of thirty-five, leaving ten children—the oldest a boy nearly grown, the next a girl not quite old enough for a cook. The woman whose husband I had bought, I had kept hired out, and knew but little about her except that she was a Negress of good taste, cleanly habits, and a good cook. She was hired by the month; and when the month was out, wife installed her as a cook, and she cooked for us one year. I have known many thieves, both white and black; but of all I ever knew, she was head and shoulder above them all. By years of practice she had reduced it to an exact science that defied detection. She had not been long in our house before she had keys that fitted all the locks on the premises. She made it a rule to gather up keys of all sorts wherever found. It was then the custom to lay in a year's supply of groceries through our commission merchant in New Orleans. From these she would steal in such small quantities that it would not be missed, as one candle at a time, one teacup of sugar, and so of everything, even of the beefsteak she fried for breakfast and which her mistress had never seen. In a word, she levied a contribution on everything that lay within her reach.

Our faithful cook, whose loss we deeply deplored and over which we and the children shed many tears, had been so strictly honest that we suspected nothing of the new one till our eyes were opened by her many thefts. No anti-slavery man has any true conception of the attachment existing in a family of the two races in such a household as ours was. Our children called their mother "Miss Bettie" and our cook "Mammie." They call her that yet. I have stood by the open graves of the millionaire, and of those whose brows have worn the wreaths of official fame; but for the first time the flowing tears and the swelling grief choked my voice when I attempted to speak of the humble, faithful, Christian slave who slept the sleep that knows no waking till the resurrection morn. My readers will kindly pardon this digression.

The remuneration I received for buying the husband of the other woman to keep them from being separated was that in one year she stole and fed to the servants of other families not less than $300 in provisions. The pay she got was that her husband ran off and left her in less than a year. In that one year I lost by the death of my cook's husband $1,400; by the absquatulation of the thief's husband, $700; and by her stealing, $300. As to the loss by the death of the faithful one, dollars have no meaning. So that often in the midst of seeming prosperity we are in the midst of adversity.

In the second year of my pastorate I bought a house and lot, for which I paid $1,600. I put about $1,000 on the premises in the way of improvements. The second year of the war I sold the place for $4,000 when Confederate money was as good as gold. I had no use for money, and deposited it, so that when I needed it, it would be on hand. The time came when I needed it very bad, but it was not money. When Congress passed the funding law, I put that with other thousands into Confederate bonds, and what became of them it is needless to say. I was compelled either to sell or rent my house. Two years before the war began, a friend of mine owned a fine farm in fifteen miles of Jackson. He had land, but not hands enough to cultivate it. My Negroes were accumulating on my hands; and as I had no land, we formed a partnership, each feeding and clothing his own Negroes, I furnishing as many horses and mules as he had, and paying him for superintending my hands. The ditching and opening of more land, putting up some needed buildings, and repairing old ones, paid for the rent of the land worked by my Negroes. This went on for two years harmoniously and profitably to both parties. It was highly satisfactory to my slaves, for up to that time they had been scattered and hired out to different persons, and some of them had not been well treated.

The election of 1860 came off, and Abraham Lincoln was chosen as President by the abolition vote. Not long after, the tocsin of war sounded throughout the sunny Southland, and the cry, "To arms, to arms, for your country, your altars, your friends, and your native land!" was heard. The secession ball in motion was set, and began to roll and rolled on and on till it crushed the hands of those who caused it first to move. It may be of some interest, at least to Mississippi readers, to have a true history of the inauguration of that fatal movement, and to it I will devote a few pages. Before doing this, however, I will finish giving the reason why we sold our city property. My nephew, for whom I was guardian, owned some Negroes, all of whom were women and children. My partner enlisted in the army, and so did my nephew at the age of seventeen. I was in the field, there was no white person on the place, and I was compelled to move my wife and children to the farm.

The people in Mississippi were divided into two parties: the Union party, led by Bell and Everett; and the State Rights party, by Breckinridge and Lane. In the city [Jackson s.d.h.] the State Rights side predominated. A mass meeting was called, and after much discussion it was resolved that a committee of fifteen be appointed to consider the whole matter and advise as to what was best to be done. In courtesy to the minority, the Bell wing were to have eight and the Breckinridge wing seven. No prominent politician was to be placed on the committee. It was to be a movement of the people. We met, and after examining the subject in all of its phases, as far as we were able, it was agreed that two of our number be selected, whose duty it should be to draft resolutions which were to be submitted to a mass meeting in the State House the following night. Judge Wiley P. Harris and myself were chosen. I presume that the reason why I was chosen was that I was the most nonpolitical member on the committee. I had never taken any part or interest in politics, had never voted for a President till the election just passed, when I voted for Breckinridge. We met and discharged our duty.

The resolutions were written by Judge Harris, with an occasional suggestion from me. Of him, nothing need be said. His reputation is too well known. If there is any honor due, it is his. If any dishonor, no man living or dead would bear it more heroically than he. Of the resolutions, I will say nothing except of the last one of the series. The Judge and myself were both the confidential advisers of Governor Pettus, and had been from the beginning of the trouble. We were, therefore, thoroughly posted with regard to the movements of South Carolina. It was the desire of the Governor of that state that Mississippi should take the initial step. Governor Pettus feared to risk his state as parties then stood—not that he or we had any doubt with regard to the almost universal desire to secede; but a great number were in favor of calling a convention of all the Southern states, and of all walking out together by a cooperation of states. The overwhelming majority, however, were in favor of each state acting in her own capacity as a sovereign, and going out of the Union on her own responsibility. What we feared in adopting their plan was that while there was no Union sentiment avowed, we did not know how much might be covered up under the cloak of a cooperation of states. We feared that said convention, instead of cooperating us out, might cooperate us in. There were also other reasons; but I am not arguing the question, I am simply giving the facts.

Had we not feared to trust their plan, and had all the Southern states agreed to secede, there would have been no bloodshed. The war was inaugurated by the North and the South being mutually deceived by lying editors on both sides. The North vastly overestimated the strength of the Union element in the South; the South as greatly overestimated, not the numerical strength of the believers in the doctrine of state sovereignty in the North, but in the strength of their backbone to stand up to their conviction. They betrayed us and themselves, and are mainly responsible for all the blood and tears which were caused to flow, for all the sighs and groans, for all the deaths and broken hearts caused by the fratricidal strife, "Beast" Butler leading the van.

But I have wandered from the resolutions, the last of which was in these words: "The fate of South Carolina shall be our fate." The meeting assembled in the legislative hall. There was no standing room for half that came. The leading lights of the state were there. The bench, the bar, the pulpit, the press, and the political rostrum were all represented. The great, grand, good, and lamented Lamar was there. In all that assembly of giant minds, but one alone grasped the situation, and that was Ex-Governor A. G. Brown. All the others never dreamed of war. They relied on the State Rights democracy, who had all their lives contended, and had gone on record by their votes, that a state had a constitutional right to withdraw herself from the compact—to be judged of her own grievances, first to seek redress, and if not granted, then to secede if she desired to do so. The sentence uttered by Lamar in his speech before that great gathering will ring in ears of many a reader of these pages: "I will pledge myself to drink every drop of blood that is shed by this act of secession." This was received amidst thunders of applause. No more popular sentiment ever fell from the lips of a man. Ex-Governor Brown remained silent at the time, but privately to his confidential friends, among whom I was numbered, he said that peaceable secession was a Utopian dream. Afterward, in addressing the assembled Legislature, he quoted the maxim, "In time of peace, prepare for war;" and added, "We are standing on the brink of a volcano, on the verge of such a war as has not been fought in all ages past." How true his prediction, how keen his perception, let history tell!

Thus the ball was set in motion so far as Mississippi was concerned. For the truth of these statements the reader is referred to the files of the Mississippian, edited at that time by the Hon. Ethel Barksdale. Both wings of the party took the stump, to use a political phrase, after the resolution passed submitting the question to the people. Prominent politicians and others were put in nomination for the convention. It was the desire of my brethren, who were all what were known as straight-out secessionists, that I should vacate the pulpit except on Sundays and take the field. I did so, and met the cooperative candidate on the rostrum as long as the campaign lasted. The struggle resulted in an overwhelming majority for separate state action. When the convention assembled, so few had been elected on the cooperative ticket that when the vote was had, they did not vote at all. A resolution was offered to make it unanimous by a rising vote, and all arose except one man. He had the nerve and felt conscientiously bound to vote "no," as he had been elected by a cooperative constituency, and his vote stands on the journal of the convention solitary and alone. He was the first man to raise a company for the war, and was elected captain and afterward colonel. How high he ascended on the military ladder, I do not now remember. I allude to Colonel Thornton, of Brandon, Miss. I do know that a truer man than he lived not, and a braver man never unsheathed a sword. He survived the war, and is living yet so far as known to me.

When the war became a fixed fact, our state treasurer resigned his office, and raised a company of the wealthiest and best-educated young men in the city [Jackson.]. He was chosen captain; and when the company was merged into a regiment at Corinth, he became a colonel. The Attorney General and myself both canvassed the state and helped to talk our people out of the Union. We were among those who would shed the last drop of blood coursing through their veins, fall back and burn everything between them and the advancing foe, die in the last ditch, be driven into the Atlantic Ocean and drowned beneath its onrolling billows, rather than submit. We said with the immortal Henry: "Give me liberty, or give me death." I was in earnest, and remained so. He was at the time, no doubt, also in earnest; but he never gave them a chance to give him death or a sleep beneath the ocean waves. I did; and if I could have had my way, I would have died in the last ditch, or my body would now be slumbering in the deep sea. When he said to me one day, "Doctor, what are you going to do?" I replied, "General, it is too late to ask that question. We have crossed the Rubicon; we have burned the bridge behind us; and we would lose, and justly too, the confidence and respect of our people, and, worse than all, our own self-respect, should we falter now. To me the last ditch would be a bed of flowers, or the bottom of the deep a bed of eider down, compared to such recreancy as this."

I had promised the boys, many of whom were members of my congregation, and the few elderly men with them, who composed Company A, that I would be the chaplain of their regiment. In compliance with this promise, after declining the chaplaincy of two other regiments, I went to Richmond, where, at the request of the men through their colonel, I received my commission from the Secretary of War and joined the command at Manassas Junction. This was the headquarters of General Beauregard, for whom I never entertained much respect, either as a military chieftain or as a man. In this respect I stood almost alone, but after developments proved that I was not far wrong.

My duty as chaplain extended no farther than preaching; any other thing done was voluntary on my part. I took upon myself various other duties, such as taking charge and control of our regimental hospital. The surgeon had the entire control of the hospital, but at the request of Dr. Holloway I relieved him of all care, except the administration of his medicine. The nurses were detailed from the various companies. The captains usually did not like to detail their best men. There would always be enough men in every company who were worthless for all camp and drill duties. It was more trouble to get work out of them than it was worth when it was done, for it was usually only half done at the best. The physician would send a requisition for a number of men needed. The colonel would send it to the captain, each of whom was to furnish his quota. Each captain called for volunteers—one, two, or three, as the case might require; and in nine cases out of ten the most worthless man or men in the company would step out—men that would eat what was prepared for the sick, drink the whisky prescribed for them, and then sit down at the card table and play poker while the sick men were calling for water or begging to have their faces washed, their heads combed, or their clothes changed, the poor fellows being too feeble to do these things for themselves. The doctor did not have his office in the hospital, which was nothing but a tent; and if he had, his duty to the sick would have prevented him from looking after the cooking, clothing, bedding, and nursing.

The colonel was also anxious that I should take charge of all these things. I told him I would do so on one condition—that he would issue an order to all the captains to detail such men as I selected; that these men be placed under me to be retained, dismissed, or sent to the guardhouse as a punishment for the nonperformance of duty; otherwise I would have nothing to do with it. He complied with my request, and I chose men who would in my judgment do all they could from principle and from sympathy with the suffering. I chose one to see to the preparation of the diet prescribed, and to see that the patient ate just what was prescribed. Ladies sometimes came in and almost killed some of my patients by stuffing them with goodies. I did not choose a cart driver or a carpenter for this duty, but a man who had run a first-class restaurant before the war. I selected another to superintend the cleanliness of the clothing and bedding of the sick, and of the floors if we occupied a house.

These reported to me daily any insubordination or neglect of duty. For insubordination they were dismissed. For gross neglect of duty I gave them thirty-six hours' solitary confinement in the guardhouse, without bread or water, and sent them back to the camp. The result of this was that when the Seventeenth Regiment, under Colonel Featherstone, had lost eighteen men, and that under Colonel Barksdale nineteen, ours, the Sixteenth, had lost only three, and yet we were encamped within sight of each other. Those regiments had chaplains, but they did nothing but preach and visit their church members. Their surgeon left the nursing to the nurses. Neither of them paid much, if any, attention to them. I visited each of the hospitals, and took in the situation. I described it to their commanders at their headquarters, but I will not describe it here. I draw the mantle of charity over it. Their position was new, and so of the surgeons and chaplains. In fact, the whole machinery was new, and ran roughly, and with much friction. Suffice it to say that I saw brave men dying, not only from disease, but from homesickness.

I made another condition when I took the responsibility of trying to save the lives of my fellow soldiers that the colonel was to visit the hospital daily when other duties permitted, pass between the bunks, and utter a few words of cheer and comfort to the men. He promised that he would do so, and he faithfully kept that promise. I said to him what I afterward said to Colonels Featherstone and Barksdale when I called at their headquarters and drew a faithful picture of their hospitals. I said to them: "Your negligence is killing the men. They have left fathers and mothers, brothers and sisters, wives and children, and those to whom they were affianced, besides state and home and friends, to follow their country's flag upheld by your hands. They find themselves sick nigh unto death on a hard and dirty mattress, with faces unwashed and unshaven, and hair unkept, the stimulants prepared for them going down the thirsty throats of brutes in human form, and the food prepared for them to eat going the same way.

Editors Note —Deleted Section Here – containing information about the terrible conditions connected with the camp hospitals— We seek that section to add here. It was excluded when printed in the pages of the Gospel Advocate in 1948 because its detail was deemed too strong for readers.

Thus neglected, on you alone they had to depend for their protection and their rights; and you failed them in their utmost hour of need. When disease reaches a crisis, as all dangerous diseases do, when nature and medicine are doing their best to win the fight for life, it requires but a feather's weight to tip the scale. The influence of mind over matter tells the ghastly tale. 'Tis death. The man feels that he is treated worse than savage beasts treat their own kind. Homesickness gathers around his laboriously throbbing heart, it ceases to beat, the brave and patriotic soldier is dead; and God will hold you accountable."

Their faces kindled with the rush of angry blood to the brain, but my age and calling prevented a harsh reply. Colonel Barksdale said: "Are you not presuming on your cloth a little too far?" I replied: "It is a duty which I owe to my cloth, as you call it, a duty I owe to you and your men, and to your and my government, a matter more painful for me to utter than for you to hear. Tell, me, Colonel, why you have lost nineteen and Colonel Featherstone eighteen, while Colonel Burt has lost but three?" The flush of anger faded from his face, he hung his head, and, rising from his seat, he grasped me by the hand and said: "From my heart I thank you. You are the bravest man among us all. It was want of thought on my part. I will set the matter right." The same in substance passed between Colonel Featherstone and myself. Both of them adopted my plan, and our losses were about equal afterward.

In addition to my hospital duties, I would get some of our sick into private families where they could enjoy social life. Apart from singing, praying, and preaching on Sundays, and our nightly prayer meeting, taking care of the sick, comforting as far as I could the dying, and burying the dead, I would get pugnacious. The old Adam would overcome the new. I would shoulder a gun and go with Company A into the fight. I do not think I killed anyone or broke any arms, but I tried to break as many legs as I could. Had all done as I did, I do not think there would have been many killed, but the number of artificial legs would have been greatly multiplied. I never could see any sense, common or uncommon, or humanity either, in killing a man in battle or breaking his arm. If you kill him, he is left on the field to take care of himself. If you break his arm, he can walk off unaided. If you break his leg, it takes two men to pack him off, and they take care not to pack themselves back till the fight is ended. I commend this mode of fighting to all who wish to amuse themselves by shooting each other.

The time of simply playing soldier was drawing to a close. We had been living in luxury, like horses up to their eyes in clover-wood hauled by the cord for cooking, vegetables were abundant, chickens and eggs plentiful, milk and butter equally so, and all as cheap as could be asked. Indeed, we felt almost ashamed to take them at the price at which they were offered. This feast of good things came to an end. The day came when the sun cast his rays of light upon the field of fight, and brave men on both sides periled limb and life for that which they believed to be the right. I enter not into any description of the struggle of the day, except that in which I was an actor, and that for the reason that it was more of a comedy to excite laughter than of a tragedy to bring tears, had it not been that valuable lives were lost.

Colonel Longstreet, in command of a brigade, was holding a ford on Bull Run. General Jones was in command of the brigade of which the Sixteenth Mississippi Regiment, commanded by Colonel Burt, and the Seventeenth, commanded by Colonel Featherstone, formed a part, also the Fifth South Carolina. The regiments were full, excepting the absentees and the sick. We numbered about twenty-five hundred. General Beauregard sent an order to Colonel Longstreet to attack Sherman's battery of eight pieces of artillery, supported by six thousand infantry and one thousand cavalry. The same order was sent to General Jones, who was guarding another crossing about two miles distant. The attack was to be made simultaneously from both points at 2 P.M. From some cause the order was countermanded as to Colonel Longstreet, and also General Jones. General Beauregard, however, failed to duplicate his courier to General Jones, and what became of the one sent, whether he deserted, was captured, or killed, was never known. We were up to this time mere lookers on, while the conflict was raging in all its fury around the stone bridge. From an elevation we could see the couriers dashing at full speed in all directions—riderless horses madly rushing over the field—the lines swaying to and fro like the waves of a tempest-tossed ocean. Occasionally the line would be broken as when a wave dashes against a rock, is hurled back, and another oncoming wave fills its place. So the lines on each side surged to and fro, at one time broken and then reinforced, till a charge was made and the other side gave way. The roar of cannon, the rattle of small arms, the gleam of the swords in the flashing sunlight, the dust and din and smoke of battlefields, have a fascination that must be seen and heard and felt to be appreciated. It cannot be described.

But the hour of action soon came for us. We were armed with muskets—a ball and three buckshot. At a distance of seventy-five yards we could break legs innumerable; at one hundred yards, a barn door would have been perfectly safe. No reconnoiter of the ground had been made. We had no artillery. We promptly moved on time, forming our line of battle in a ravine running across an old field about a mile in width. We supposed that the battery to be taken was about four hundred yards from the ravine, in which our battle line was formed, under cover of an elevation. I presume the conclusion was reached by General Jones that the battery was on this side of another ravine. We could see a few large trees and many small ones whose tops were visible over the elevation in front of us. We were ordered to march in common time till we reached the level ground, and then to charge with fixed bayonets; and such a charge, my countrymen, was never made since time was young and the world was a babe, and never will be again till time dies of old age. It was not at a double-quick, so that the distance could be observed and lines straight; it was a blind, maddened rush forward, as though pursued by the furies, every man making a beeline for the place where the treetops were waving in the breeze. The men were yelling and firing their guns, and there was as much danger of death in the rear as in the front. Poor Eddie Anderson, a nephew of President Davis, was mortally wounded by one of our own men, and died that night.

As soon as we appeared above the elevation under which we formed, they opened on us with their artillery and six thousand minnie rifles. The shot and conical shell plowed up the ground like some newly-invented infernal machine. They would ricochet and plow it up again, and then bury themselves in the ground. We lost some killed and many more wounded, the number not remembered. It was fortunate for us poor fools that the battery was far away from where we thought it was, or few would have been left to tell the story of that fearless and foolish charge. Our loss was while we were passing over the level ground which was but a short distance till it declined toward the second ravine, ranging from twenty to forty feet in depth, in some places perpendicular, in others more so. It was overgrown with some large trees, many small ones, bushes and briars innumerable, and had a six-rail fence running along the brink. Here we were saved from their death-dealing fire. They could not depress their guns, but continued to plow up the ground in our rear. Up to this time I had not fired a single shot. I could see nothing at which to shoot. Although the men were blazing away all along the line, I was armed with a Colt's rifle, double-cylinder, eight charges for each, one of them in my gun, the others in my pocket, and two navy sixes in my belt. I was standing near a large tree. The saplings and bushes were so thick that I could not see their line. I did not think of the big tree, but learned more sense afterward. I stepped down a few paces where there was an opening; and as I passed the corner of the fence, a grapeshot struck the top rail, shivering it into kindling wood. Thinks I: "You saved your long legs by that move."

I passed through the opening and saw their lines about six hundred yards from where we were. I delivered five shots, but shot low. There were three long-range guns in the brigade, and somebody killed three of the Federals and wounded some others. Suddenly the firing ceased on our side. I paused and looked to my right. Not a man was visible. I quit firing and faced-about. The order had been given to fall back, but I had been so deeply interested in trying to break some of their legs—I thought they had no business to be there—that I did not hear the order. It had been promptly obeyed by the men. They went, and did not stand on the order of their going—not much. It was every man for himself, and the Yankees or his brimstone majesty take the hindmost. I was mad all over and clear through. I shouldered my rifle and marched down the hill as stubborn as a mule. A conical shell came shrieking over my head, plowing up the ground about twenty feet in front, and another passing to my left, the wind of which I thought I felt. I thought it was folly for me to show so much pluck where there was no one to applaud; so I quickened my pace, jumped down into a ravine six feet deep, struck a dogtrot, and soon reached the brigade. Everything was confused and mixed up—colonels and captains and other officials rallying their men and getting them into line beyond a skirt of timber to guard against an expected cavalry charge.

I looked across the old field toward our camp from which we had marched to the place where the fight and the footrace had just come off. I saw the rear of a line of men—how many in number, I know not-just passing out of the old field into a narrow wagon road which ran for fifty yards through a chaparral of bushes and briars so thick that a rabbit would have left his fur running through. I found out that these men, belonging to no particular regiment or company, when the order was given to fall back, outran the others and got mixed up together. When the officers halted their men and formed them into line again, these men, supposing that they were all going back to camp, did not wait for orders, but onward went their own way. I called the attention of the officers to this retreating column. Their reply was: "We can't help it; we must get our own men into shape." Seeing the adjutant of the Fifth Carolina Regiment sitting on his horse, I stepped up to him and asked him to overtake these men and bring them back. His reply was: "I tried to stop them, but they are as deaf as adders." "Dismount," said I, "and give me your horse, and I will bring them back." Mounted on his horse, I dashed across the field and overtook their rear just as they were entering the narrow road that passed through the thicket. I called on them to halt, but to this they paid no attention. I rode rapidly round the thicket, and at the terminus threw my horse across the road, his head in the bushes on the one side, his tail in those on the other. I drew one of my six-shooters; and when the three in front came within ten feet of me, I leveled my pistol and called out: "Halt! I will bespatter these bushes with the brain of the first man who moves a step farther!" They threw up their hands and said: "Don't shoot!'' In a few words I explained the situation and made an earnest appeal to their patriotism and state pride. They faced-about, and in double-quick time, with a rebel yell, went back and found their places in the newly-formed lines.

A courier had been sent with a flag of truce to the battlefield to ask permission of the enemy to let us care for our dead and wounded. I found the officers anxiously awaiting the return of our flagbearer. Just as I got there he came up and reported that the field was as bare of men as the palm of his hand. And here comes in the comedy, or, more correctly speaking, the farcical part of the program. While we were forming our line of battle they received a telegram to limber up and make for Centerville in all haste. They could not retreat till we were repulsed. They waited till we charged upon level ground, and then opened fire as described. All this occurred in less than twenty minutes. While we were tumbling downhill in confusion worse confounded, they were traveling toward Centerville, much worse scared than we were. The fight ended at the stone bridge. The panic had set in, and the Bull Run races were open to all who desired to enter for the stakes.

One major resigned a few days after this, and the regiment kindly tendered me the office for what they called an act of heroic bravery on the field of battle. I thanked them, but declined the honor. I said to them: "My more than brother and bosom friend of thirty years' standing would give me any office that I could fill, but I hold an office higher than any that he can give. I would not exchange it for the crown of a king, nor for the presidency of a republic." I was called "the fighting parson" from that time till the close of the war.

>

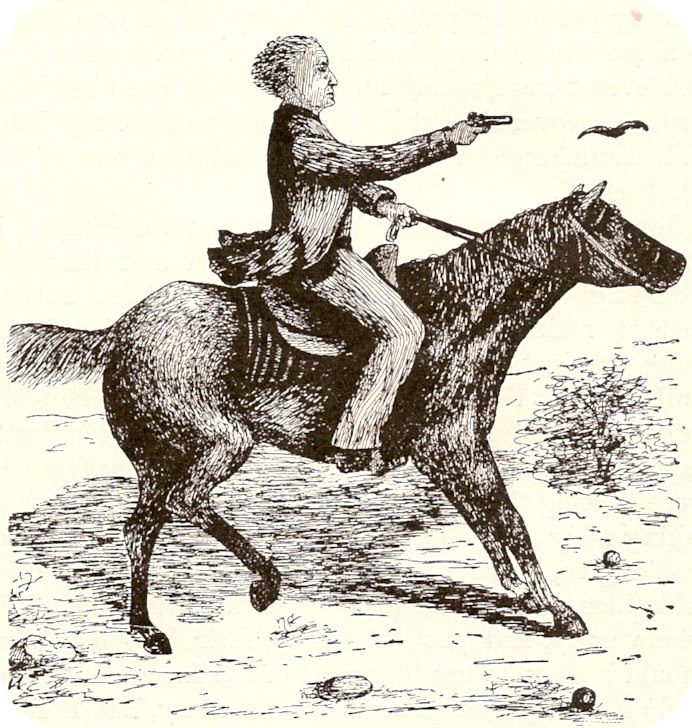

Seventy Years In Dixie Illustration Of The "Fighting Parson"

![]()

An Excerpt From Seventy Years In Dixie, Chapter 28: Story Of The War

The story of the war would hardly interest the reader. It has been told so often that nothing new remains to be said. It was a gloomy time in Dixie. Only those who lived through those troublesome times in the South can ever know fully what the war really was. I shall, therefore, hasten over that, to me, ever painful period in the "Seventy Years in Dixie." I have no desire to linger upon the memories of the war. Many mistakes were made, vile sins were committed, and not a few deeds of love were done which show the divine nature that is in man all the brighter because of the darkness and gloom of the environments.

During the war I did what I thought to be my duty, but when I was mustered out of service, I shed bitter tears of defeat and disappointment over the grave of "the lost cause," and solemnly resolved to fight no more. War is a terrible thing. The life of a soldier was not calculated to increase my piety. My environments in the army were not at all favorable to the development of the better elements of my nature. Fighting, as a regular occupation, is a bad business every way. It calls out all the latent meanness in the human species. It can never be defended or excused on any other ground than as a choice of evils, and in the light of my experience I am disposed to hold that it is the last choice a man should make.

I enlisted in the army as a preacher of the gospel, and was assigned the duty of a chaplain. It was the hardest place to fill in the whole army. I was expected to cut my sermons to fit the pattern of our occupation as soldiers. It was a hard thing to do. It was expected that my preaching, prayers, and exhortations would tend to make the soldiers hard fighters. It was difficult to find even texts from which to construct such sermons. I soon discovered that I would have to close my Bible and manufacture my ministerial supplies out of the whole cloth.

Some of my preaching brethren told the soldiers, in their sermons, that our cause was just, and that God would fight our battles for us. I never did feel authorized to make any such statements. I believed our cause was just, of course, but I could see as clear as a sunbeam that the odds were against us, and, to be plain, I gravely doubted whether God was taking any hand with us in that squabble. I told some of the preachers who were making that point in their sermons that they were taking a big risk. I asked them what explanation they would give if we should happen to get thrashed. I told them such preaching would make infidels of the whole army, and put an end to their business, if we should happen to get the worst of the fracas. I wanted to do my duty as a preacher in the army, but I did not want to checkmate the ministry in case we should come out second best in the fight. I think a preacher should always leave a wide margin for mistakes when it comes to interpreting the purposes of God beyond what has been clearly revealed in the Scriptures. It is not good policy for a one-horse preacher to arbitrarily commit the God of the universe to either side of a personal difficulty, anyhow. I told the soldiers plainly that I did not know exactly what position God would take in that fight. So far as I could see, the issue was a personal matter between us and the Yankees, and we must settle it, as best we could, among ourselves.

It was not difficult to see how this line of argument led me away from the true spirit of the ministry, and thoroughly aroused within me a desire to fight. It became clearer to me every day that one good soldier was worth a whole brigade of canting chaplains, so far as insuring the success of our army was concerned. If I must preach to others so as to make them good fighters, why not give them an object lesson on the battlefield myself? My premises may have been wrong, but my conclusion was certainly not illogical.

So I asked for a gun, took a place with "the boys," and was dubbed the "fighting parson." At Bull Run I stopped the fragments of a stampeded regiment at the muzzle of a revolver, and I led them back into the fight. I have no idea how I looked; I do not want anybody to know how I felt. The imagination of the artist is wholly responsible for the illustration of that scene in my eventful career. I have made no suggestion; I offer no protest; I ask no explanation; I attempt no defense.

I have no evidence that I ever killed or wounded anyone during the war. I sincerely hope I never did, and deeply repent the bare possibility of such a thing. I want no fratricidal blood on my hands. As I now stand trembling upon the verge of the grave and look back over the dreary years of an unprofitable life, I weep over my many blunders, look trustingly to God for mercy, open wide my arms to a sin-cursed and sorrow-burdened world, and in the tenderest love for all and with malice toward none, say: "We be brethren." The war was a mistake and a failure. All wars are mistakes and failures. They may sometimes be necessary evils; but if so, it is only because a man's wickedness makes evil necessary. A heart weariness and soul sadness no pen can describe come over me when I think of those dark days of bloody war with their tiresome marching, wasting disease, cold, hunger, and consuming anxiety.

I pass now to the last year of the struggle. Most of our slaves had left us. My nephew owned two women. One of them had two grown children—one a boy, the other a girl who had one child. The boy went to the Federals. We concluded to dissolve the partnership, of which I have previously written, and quit farming. This was in the spring of the last year. The previous winter, I sold to the government eighty-three hogs averaging two hundred pounds. When we divided assets, I sold corn, fodder, peas, potatoes, horses, mules, wagons, and all my part of the cattle that would do for beef. My other cattle and my stock hogs I sold, retaining nothing but two of my best milch cows. I then removed to Meridian, Miss., so that my wife and children could be under the protection of her youngest son, who was the express agent at that place, and had been from the beginning of the war. My health failing, I was transferred from field to post duty, as chaplain of the hospitals, of which there were two. I was there with wife and four children, two of the daughters of my cook, one of them with two children, the other single, and four of my cook's smaller children, ranging from twelve down to four years—fifteen in all. One of my fine cows killed herself eating meal in a soldiers' camp, into which she had made a burglarious raid. It was a Federal soldiers' camp. The bottom of the Confederate tub had fallen out, the hoops had fallen off, and the staves were scattered around loose like the fellows' milk. I sold the other cow for forty dollars; and my wife's oldest son had given her some time during the war, twenty dollars in gold—just enough "mit a tight squeeze," as the Dutchman said about Jake Snider's getting to heaven—to bring us back to Jackson.

When I reached Jackson, I was houseless, homeless, and penniless; but, thank God, not friendless. A dear old wealthy sister in the Lord, a widow and childless, was much attached to me and mine. In order to keep us near her farm, eight miles from Jackson, she gave me a fine plantation with an elegant dwelling and all needed outbuildings within one mile of her residence. It would have sold for fifteen thousand dollars before the war. She gave for it seven thousand dollars in gold. Fatal gift. I could not get old clothes for preaching. All hands flat broke! I was in a worse condition than the Indian preacher. When asked how much he got for preaching, he said, "A suit of old clothes." "Poor pay," said the inquirer. "Poor preach, too," said the Indian. I could not even get that, for each one had to wear his own suit of old clothes. I felt that the time had come when I was released from my vow. I could no longer keep soul and body together. I decided to go to the practice of law. I had baptized a leading lawyer in 1856, Judge George L. Potter. The Sunday after he was baptized, he led in prayer. He soon developed into a first-class preacher, preaching on Sunday and practicing law through the week. He continued this till he went to his reward. I rode into the city, and proposed a partnership. He said as a general rule he was not partial to partnerships. Neither am I except with a woman as a wife. He asked if I proposed making law the business of my life. I said: "I desire to use it to support me in preaching. I want you to do the office work, prepare the cases, and hunt up the authorities. I will aid you in the pleading. In the interim between court terms, I will hold protracted meetings, and we will both preach on Sundays. Our partnership will be for time and eternity. Whatever good I may do, if any stars are added to my crown of rejoicing, I will ask the Master to give one-half to you." He said, "I will do it."