Samuel W. Womack

1850-1920

[need photo]

![]()

S. W. Womack was born around 1850 near Lynchburg, Tennessee. He was the son of Berry Womack, his mother being unknown. He was married to Sallie J. Tucker. Her mother was Harriet Tucker, and her father is unknown. "Aunt Sally," as she was referred to, gave birth to three children, Philistia, Minnie, and Elnora, who died in infancy. Minnie grew up and attended Fisk University in Nashville. She graduated at the age of eighteen and married an up and coming young preacher by the name of Marshall Keeble.

Before moving to Nashville, Womack served as a school teacher among the African-American children of Fosterville in Rutherford County, Tennessee, near Lynchburg. In the area, the preachers among churches of Christ were men like R. B. Trimble, T. W. Brents, T. B. Larimore and T. J. Shaw. Being an educated black man, it was not long before he began preaching the old-time gospel to his neighborhood. After moving to Nashville he preached the gospel full time. (RJR, p.2).

Living in the days of reconstruction in the south, the relationships between whites and blacks were strained. Financial struggle was a challenge to all, especially among the African-American people. Perhaps the struggle was what caused the gospel to spead among black and white. It was in this era that S. W. Womack grew to prominence among his people. The particular date of his conversion is unclear, but it was reported by Marshall Keeble at his death in 1920 that he had evangelized for forty years. Thus, it was probably in the late 1870s when he heard the gospel proclaimed at his home near Lynchburg, though some have suggested it to be much earlier. Being astute in all his ways, he carefully wrote down the Scriptures he heard preached, going home and studying them. Finally, it was Thomas J. Shaw who immersed him in Christ for the remission of his sins. Very soon thereafter Samuel began preaching the gospel.

Moving back to Davidson County, he joined himself with the Gay Street Christian Church. Another black congregation, the Lea Street Christian church was near. The preacher there was Alexander Cleveland Campbell. The two them gained a great friendship and shared a wonderful afinity for the work of the Lord. The styles of the two highly complimented one another. Campbell was the more dynamic of the two. It was said that when he preached, he was known to move up and down the aisles of the building, jumping up and down to make his points. Womack's classroom demeanor easily transfered to the pulpit for a more analytical approach. Both these men traveled a circuit where they would preach for different churches in the area.

Among the black brethren, perhaps the best known name in the brotherhood at that time was Preston Taylor. Before coming to the Lea Street church, Taylor had made a name for himself as one who had come from slavery days, and because of his entrepreneurial skills, showed that the black man could advance himself in the world quite successfully. He was also a dynamic speaker and minister. Moving from Mount Sterling, Kentucky, he became the minister for the Lea Street Christian Church in about 1884. Not long after his arrival, the church began experiencing unrest over the instrument of music. In addition, Campbell became greatly concerned that when Taylor was away, fill in speakers sometimes included denominational preacher. With similar problems over the instrument were taking place at Gay Street, Campbell and Womack pulled their families away and began the Jackson Street church of Christ in 1906. In the process of the move, one of Taylor’s converts, Marshall Keeble, was admonished to give up the instrument, and followed the elder preachers in the building up of the non-instrumental work. Perhaps one of the biggest reasons they were able to reason so well with the younger preacher was because Keeble had married Womack’s daughter Minnie in 1896.

After a few years, A. C. Campbell left to settle in St. Louis, Missouri, leaving Womack and Keeble in charge of the Jackson Street work. Both men tirelessly devoted themselves to the building up of the cause. At Womack’s death, Marshall Keeble surmised that S. W. Womack was to the black brethren what David Lipscomb was to the whites. Womack and Lipscomb were close personal friends. Many times Womack was known to visit the offices of the Gospel Advocate, where he would sit down and study the Scriptures with Lipscomb. This tied them closely together for many years.

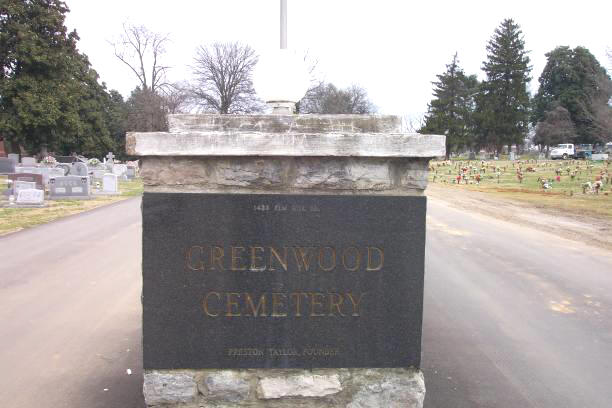

Late in life, Samuel Womack developed cancer of the lower bowel and rectum. He suffered greatly with it for a couple of years before succumbing to it in death, July 13, 1920. Present at his funeral were A. M. Burton, F.W. Smith and A.B. Lipscomb, the latter two having speaking roles. His body was laid to rest in the Greenwood cemetery, a graveyard that had been founded some years earlier by Preston Taylor. This cemetery would later play host to many good brethren from among the black brotherhood including Marshall, Minnie and Laura Keeble, the last of which was his second wife. Minnie and some of the Keeble children are also buried there in unmarked graves, in another location of the cemetery. Thus, they are not buried near Marshall and Laura, who are buried together.

-Scott Harp, webeditor, TheRestorationMovement.com

Source: (RJR) Roll Jordan Roll, J.E. Choate c.1968, Gospel Advocate Company.; S. W. Womack's death certificate, available on Ancestry.com; and other sources.

![]()

S. W. Womack's Part In The Work Below The Mason-Dixon Line

"When J.M. McCaleb visited the Jackson Street Church in 1911, he said that S. W. Womack "is to the colored people what Brother Lipscomb is to the white people," for Womack was "a man with a good name." (J.M. McCaleb, "Brother S. W. Womack and His Work," Gospel Advocate, LIII (Jan. 19, 1911), 75) It had been in 1865 that T.W. Brents and Robert Trimble went to Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, to conduct a meeting for the blacks that Womack heard his first pure gospel sermon. He was baptized in the fall of 1866 by a white preacher, T.J. Shaw, "the man with the old Book in his head." For several years the whites and blacks worshipped here together and Womack would long remember that "the attitude of the white people of that churhc toward the colored people was then, and is now, a great uplift to me." (S. W. Womack, "Attitudes of the Races," Gospel Advocate, LVII (Dec. 30, 1915), 1326,7) Following the lead of his white brethren, Womack also accepted innovations until he met Alexander Campbell. Campbell studied himself out of the Christian Church in 1900 and began holding services in his home on Harder Street in Nashville. His influence on Womack led him out of the Christian Church, too, and the two men took the lead in building up the Jackson Street congregation." (Alexander Campbell, "Work Among The Colored People," Gospel Advocate, LI (Dec. 2, 1909), 1523) The two were joined later by G.P. Bowser who had joined the Methodist Church in 1889, studied enough to be licensed to preach in 1892, but who, by his Bible study and some help from Samuel Davis became a member fo the Gay Street Church in Nashville in 1897. When he disagreed with the organ and the society in the church, he left it." (G.P. Bowser, "As Ye Find Christ, Walk in Him," Gospel Advocate, XLVI (Mar. 24, 1904), 190.) He became one of the trio, with Womack and Campbell, who forged a dynamic work with the black southern Christians."

-Earl I. West, Search For The Ancient Order, Vol. III, Excerpt from Chapter VI, "Below The Mason-Dixon Line," pages 179,80

![]()

Brother S. W. Womack and His Work

It was my privilege while in Nashville, Tenn., to speak one Sunday afternoon to the colored brethren on Jackson Street. This church is mostly indebted to Brother S. W. Womack for its existence. One of the white brethren who went along with me remarked: "Brother Womack is to the colored people what Brother Lipscomb is to the white people." For a long time I have been reading Brother Womack's notes to the Gospel Advocate, and have been interested in his work. He has built up a good name right where he lives, and is a benefactor to his race. He is not only laboring for the uplift and salvation of the American Africans, but is deeply interested in the Africans in Africa. He hopes soon to have the colored churches here support a missionary there. Brother Womack is a laborer worthy of his hire. The colored churches are usually poor. If some white congregation would make him their evangelist and see that he receives at least a modest support, it would be a good work. The colored churches would do something; what they lacked could be supplemented by some white congregation.

-J. M. McCaleb, "Brother S. W. Womack and His Work," Gospel Advocate, LIII (Jan. 19, 1911), 75

![]()

Among The Colored Folks

A Report From S. W. Womack:1920

Two months of 1920 have come and gone, and I have not been able to do anything in the way of preaching and holding meetings; but a few of the brethren, sisters, friends, and churches still remember me. Beech Grove Church, near Brownsville; the church at Lebanon; and Jackson Street Church, in Nashville, give a monthly contribution. A few of the thankful, not only to these, but to all others who have helped to care for us, and we are still looking to the good Lord for his care. The services at Jackson Street Church for these months have been fairly good. On the first Lord's day in January and the second Lord's day in February, Brother James Gant preached for us; on the third Lord's day in February, Brother Thomas Harris; on the fourth Lord's day, Brother Haley. The work is moving on fairly well. Brethren, let me hear from you, and let me have your prayers. My address is 1508 Hamilton Street. S. W. WOMACK. Members at Christian College and Harris Chapel remembered me during the holidays. These offerings were" small, but helpful.

I have been encouraged. Brother Larimore writes: "Wife and I are sending you our contribution for the last quarter of 1919 and for the first quarter of 1920. Be of good cheer:' Brother B. F. Hart writes: "Inclosed you will find a check, and you must not think, because you are not able to be out on the field, that I am not going to help you." Brother Martin, of St. Marys, W. Va., says: "As long as I have a dollar, you have one." Brother Fletcher Williams faithful are always Sister Peebles and says: "The remembered." daughter, of Smyrna, write: "Let us hear from you." The little band in Detroit, Mich., through Brethren Keeble and York, remembered me. The South College Street sisters are mindful of me, as is Brother S. P. Pittman, of David Lipscomb College. We are so thankful, not only to these, but to all others who have helped to care for us, and we are still looking to the good Lord for his care.

The services at Jackson Street Church for these months have been fairly good. On the first Lord's day in January and the second Lord's day in February, Brother James Gant preached for us; on the third Lord's day in February, Brother Thomas Harris; on the fourth Lord's day, Brother Haley. The work is moving on fairly well. Brethren, let me hear from you, and let me have your prayers. My address is 1508 Hamilton Street.

-S. W. WOMACK.

-Womack, S. W., “Among The Colored Folks,” Gospel Advocate, March 20, 1920 pages 262,263![]()

Restoration History Among Blacks

Introduction

The subject of Restoration History among Blacks is one of the most rich and yet neglected subjects in the field of Restoration History. It is not because Blacks do not have any history to report. There is much which Blacks have accomplished toward the restoration of New Testament Christianity. It is a tragedy that these accomplishments, for the most part, have gone unnoticed and have not been recorded. There is an urgent need for more writing to be done in this area.

As far as I have been able to determine there are about three written works where information on this subject can be obtained. The Christian Echo, a black religious periodical that was founded by G. P. Bowser in 1902, and edited by him until his death in 1950. I was not able to secure volumes of the Echo for this material. Another source of information is the work by J. E. Choate entitled "Roll Jordan Roll" which is a biography of the late and beloved Marshall Keeble. I have drawn from this work extensively and do express my appreciation to Brother Choate for having written this book. The other source that I found to be available is the Gospel Advocate. Reports from some black preachers concerning their work were recorded in the Advocate. I hope that the materials here compiled will be sufficient to motivate enough interest for our discussions, and that more probing and digging for factual information on this important theme will be forthcoming.

Early Beginnings

Blacks in the beginning became members of the churches of their masters. Citing one specific instance, the historian, Robert L. Jordan, makes this generalization concerning the first period of black church life:

"In these early days slaves drove their masters to the services, others living near came and stood on the outside while several went in to assist with the children or to do any other kind of work assigned. Some of the slaves being deeply impressed, sought spiritual guidance. They were already in Hades and to hear a man of God tell them how they might secure peace and sit down at the welcome table pleased them very much. They did not choose to go to a torment greater than the one already experienced. It had been hard to understand the preaching, but now this simple way of telling the old, old story appealed to most of them. Several were added to the church. Often these went back and told the news to the other slaves. Many believed and were baptized; others were taught by the masters and their families. At times the most gifted among the slaves were trained and allowed to preach to the rest. Occasionally slaves were gathered in separate buildings and were preached to by the evangelists either before or after the regular service."1

Blacks were included into the membership of the Brush Run, Pennsylvania Church and also, the Cane Ridge, Kentucky, church where Barton W. Stone was the minister.2 Stone as well as Alexander Campbell were slaveholders. An interesting evidence of the reception of black members by white preachers is the testimony of G. A. Goins of California, an ex-slave. He said, "Mr. Campbell was a great debater. I saw him many times, with his own hands, baptize black Men and Women. I never tired of hearing him speak. He always had something to say."3

There were black members of white churches in many places like Cane Ridge, Kentucky. An interesting thing happened at Burlington, Ky. that proves to the contrary. Thomas Campbell appears to have followed his Christian convictions much more closely in reacting against slavery than did his son Alexander. In the summer of 1819 Thomas Campbell was attracted by a group of blacks amusing themselves in a grove, as was their Sunday tradition. Out of his native impulse he asked them to come into his schoolroom to hear the Bible read. They accepted his invitation and stayed for a hymn sing. On the next day Campbell was told by a friend that it was against the law to teach Blacks except in the presence of one or more white witnesses. He was greatly shocked to learn that the free preaching of the gospel was illegal in portions of the United States. He decided to adhere to the principle and shake the dust from his feet and settle down some place else. Much to the regret of his family, he resettled near West Middletown, Pennsylvania, in upper Brush Run Valley. There were few slaves in this territory since it was near the border and easy for them to escape. The few found here were an exception, and treated much like the free laborers, although the law forbade teaching them to read, no one was molested for doing it.4

Although Blacks were admitted membership into White churches, the names of their owners were also recorded with their names as 'such; Male: Dick (Dunn's), Anderson (free, black), Female: Priscilla (Dunn's) etc. These black members were also segregated in the auditorium or some other place by several means. There is much evidence to prove' that slaves were separated from other members in the back of the auditorium, in a balcony, if the building had one, or in an additional building attached for this purpose.5 It was suggested, that a slave could better reach or approach one of his own group. Therefore, Black members were instructed to teach their own group. One such instance is Alexander Campbell, a slave, that was converted at Cane Ridge was freed to do missionary work among the Blacks. At Midway, Kentucky the church became large and the Whites provided money to erect a building for their black members. This ex-slave led in the building of this meetinghouse and added three hundred more members.6 This separation of Black groups, when they were large in number, from white churches began before the Civil War, and emancipation precipitated the procedure generally.7

Those churches having Black members did not abandon its Black member all at once but used a gradual process. When the number of Blacks began to get large, the Whites would encourage them to form their own church. They thus became a mission supported by the White church until it was able to support its own work. This was practiced continually until the Blacks volunteered to leave. This separation took many years to complete. During the days of reconstruction many Blacks denounced "Ole Massa's" baptism and were baptized again by a black preacher.8

After the Blacks were established in their own meeting houses many problems arose. There were the problems of maintenance, education and evangelism. The change was desirous, but most of the leaders could not read. They were limited, in their training. They only knew what they were told about preaching and singing. They were unable to develop effective worship programs and to handle business matters. Therefore, they were left confused and frustrated.9 The tragedy of this kind of thing is that in many, many places at home and abroad these circumstances in young and some old congregations have not changed a great deal.

After these separations began to occur in the pre-civil war days, the question of slavery arose among the White brethren. They tried to determine if it was scriptural to have slaves. This question came up early in 1845. Both Thomas and Alexander Campbell expressed their views upon the subject and dropped it. In essence Thomas Campbell decided that God had allowed slavery at certain times as a punishment for sin and that the descendents of Ham, therefore, were being punished by those of Japheth and Shem down to his day. He also concluded that to hold slaves was divinely permitted. Alexander concluded that slavery was not a moral issue but a political issue. In this he was saying that slavery was neither right nor wrong in and of itself, so far as the scriptures taught. The settlement of such issue would be the responsibility of the government.10

About five years later this subject came up again. The Congress had just passed the Fugitive Slave Law making it lawful and compulsory for a person who found a slave who had run away to return him to his owner. If he did not do so, a fine was leveled against him. The law caused a lot of confusion. Because the Northern brethren said it was sinful to own a slave, therefore, to return one who had escaped was also sinful. Of course, Campbell disagreed. He pointed out that the government was ordained of God, and Christians should obey the Fugitive Slave Law.11

Regardless of how the Northern or Southern brethren viewed slavery, it was being practiced and the spreading of the gospel among Blacks (slave & free) was being retarded. Another interesting fact was that the Civil War was at hand and the work of the church among all, White and Black, would be hindered. During this period of time not much is available concerning the restoration history.

As has been stated earlier the separation of Blacks and Whites started before the Civil War. After the war the slaves were freed and the emancipation was signed. This precipitated the separation procedures.

The White disciples of Lynchburg, Tennessee, supported a protracted meeting, as it was called at that time, at the close of the Civil War, in the summer of 1865, for the Black people there-the first for them. Preaching in this meeting was done by brethren T. W. Brents, R. B. Trimble, and "Old Father" Lee, as he was called.12

There were any number of preachers and churches in various places throughout the South. Some of the preachers that helped to bring the Black people into the church and through the Civil War were the Loweries, Jones, Daniel Watkins, William and Henry Lewis, and others.13 There is not much information about these men or their work. Their names have only been mentioned as preachers among the Blacks during this period of time.

In an article written by J. N. McFadin to the Gospel Advocate in 1868 one finds reports of the work among Blacks for the year 1867 in Circleville, Texas. McFadin said that on the fourth Lord's day in September N. Howe and T. Kuykendall held a meeting in his house and four Blacks were baptized. He further stated that there were three black preachers in that area, the other being James Davis. It seems to have been the practice of McFadin to report the progress and work among Blacks along with his reports to the Advocate.

In the January 1868 issue of the Gospel Advocate there appeared a letter from George Ricks of Tuscumbia, Alabama, requesting help on their meetinghouse. At this time there were about fifty members in their church. The writer has preached in this area of Alabama and is acquainted with the Ricks family. I have had the opportunity to visit the grave site of Elder George Ricks. I have seen a portion of the Old Blacks home place. Percy Ricks told me that his grandfather was baptized by Preston Taylor and that Taylor was baptized by Campbell. George Ricks was preacher to the first Black congregation in the State of Alabama. He was born 1838 and died in 1908 after baptizing his grandson Percy in 1907. The Ricks family has been instrumental in spreading the cause of Christ for many, many years.

The year 1868 seemed also to be a time of debate between the Northern Whites and the Southern Whites over which were doing the most to help the Blacks in their separate congregations. In a letter written to the Gospel Advocate by J. S. Havener of Atlanta, Georgia, it was reported that it was difficult for Whites to work with Blacks.14 In an earlier article David Lipscomb responded to an accusation made by some of the Northern brethren that the Black disciples were no longer permitted membership in the White congregations of the South. Lipscomb told these accusers that in the states of Tennessee and Kentucky there were Black disciples and many preachers, also, of the Black race.15 It is not clear if he meant Blacks were members of the church or members of White congregations.

Campbell and Womack

Our attention now is directed to four men who got the restoration of New Testament Christianity among Blacks off to a good start and firmly established in these beginning and early days. These men were Alexander Cleveland Campbell, better known as Aleck, S. W. Womack, G. P. Bowers and Marshall Keeble.

Aleck Campbell deserves first honors for starting the Restoration of New Testament Christianity among Black people in North Nashville around the turn of the century. Aleck Campbell, his wife, and mother were baptized in Wartrace, Tennessee, by D. M. Keeble, an uncle of Marshall Keeble. Aleck obtained employment in Nashville and moved his family there where they began worshiping with the Lea Avenue Christian Church.16 It is highly possible that this Campbell is related in some way to the Campbell (ex-slave) that was baptized at Cane Ridge, and later freed to do missionary work among Black people.

The issues of "music and society" did not bother the black disciples in the back country away from Nashville. There are three basic reasons why they did not. In the first place, Blacks were not financially able to afford organs and pianos. Secondly, they could not play them, and thirdly, they were very limited in their missionary work and travel.

In Nashville of course, the situation was much different. There were two well established Christian Churches; the Lea Avenue and Gay Street Churches. They were clearly identified with the Disciples of Christ.

Aleck was the first Black Christian to withdraw from the Disciples of Christ because of "unscriptural innovations." He was convinced around the turn of the century that the Disciples of Christ were engaged in unscriptural religious practices. His daughter, Alexine Campbell Page who passed away in this decade, said that her father some how came under the influence of David Lipscomb and those associated with him in the Gospel Advocate.

Aleck Campbell withdrew from the Lea Avenue Christian Church when guest preachers from denominations would preach in the absence of Preston Taylor, the regular preacher. The last time that he attended a service in the Lea Avenue building, he stood and challenged these unscriptural practices. The organist and choir were directed to drown out his words. He then left the services and never returned nor allowed his family to return.

He thus started worshipping in his home on Hardee Street with his wife, mother, sister, and daughter after the order of the New Testament. In describing Aleck, B. C. Goodpasture as a child remembers hearing him preach. He was the first Black preacher that Goodpasture had heard. Goodpasture remembers him as being a top notch preacher.

Campbell's work as a preacher was very. widespread. He conducted meetings in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Arkansas. One of his favorite places of preaching was down at the end of Broadway Street at the Cumberland River where men came to loaf and pick up odd jobs. He was an excellent "street corner" preacher. Aleck is given credit for establishing the Twelfth Avenue South church which meets today on Lawrence Avenue. In 1906, C. A. Moore, a trustee of the old Nashville Bible School, gave Aleck a tent to use in his meeting work. Aleck pitched that tent on Horton Street and stayed there from September until December with fourteen baptisms that begun his very fine congregation.17

Shortly after the protracted meeting at Lynchburg in 1865, S. W. Womack was baptized by T. J. Shaw. There is not much information available concerning the family background of this great restorer. Womack and his wife, Sally, had three daughters, Philistia and Minnie who lived to be adults and Elnora who died as an infant. Womack moved to Nashville from Fosterville in Rutherford County, Tennessee. After coming to Nashville, Womack gave up teaching which he had done around Lynchburg and began to preach full time.

He won the friendship of the White disciples from the very beginning. He worshipped with them often and later his reports appeared in the Gospel Advocate.

Womack withdrew from the Gay Street Christian Church where he and his family had been members since moving to Nashville. They joined hands with the Campbells who had withdrawn from the Lea Avenue Church. Aleck Campbell and S. W. Womack were unwilling just to "withdraw." They then made it a practice of going from house to house to convert others.

Womack proved to have as much influence as Aleck Campbell. In 1904 he preached in a meeting three weeks at the Jackson Street Mission. Womack was soon preaching far a field in Middle Tennessee. He preached in Davidson, Wilson, and Putnam counties in the summer of 1905. In early winter Womack returned to these places where he encouraged the new converts to attend the church services regularly, and to make weekly contributions.

Each year found Womack launching out a little further to preach the gospel. By 1908 Womack was in full swing of things in Arkansas. There he preached in forty-three religious services. He was in the state of Alabama by 1910, in the area of Mumford, Silver Run and Rogersville. The black churches welcomed Womack everywhere he went.

S. W. Womack won the respect and support of David Lipscomb. The South Street College Church of Christ where Lipscomb served as an elder was helping to support Womack and Campbell along with the Tenth Street Church.18 Womack in his reports to the Advocate frequently mentioned the encouragement that he received from David Lipscomb. It was always a delight for Womack to visit the Advocate's Office where he often came for advice from Lipscomb and E. G. Sewell.19

Womack had nothing but praise for these men and the Gospel Advocate. He complimented them in 1916 for allowing the reports of many black preachers to appear in this paper. He said men before him like the Lowries, Jones, Daniel Watkins, William and Henry Lewis and others were able to make their reports to the Advocate.

Campbell, Womack, and Bowser were the first black preachers to be generally recognized by the White brethren after the Civil War. They received from White brethren their major support .20

It became very apparent that by 1914 the struggle to restore New Testament Christianity among Black people was grimly anchored .21

Bowser and Keeble

Much of the history of the black church owes its respect to G. P. Bowser and Marshall Keeble.

Bowser is credited with being the father of Christian Education among Black people and the founder of The Christian Echo, the only Christian periodical edited and published by Blacks.

Keeble is remembered for his work in Christian education as President of Nashville Christian Institute, lecturer, debater and evangelist."22

The influence of G. P. Bowser among Black disciples in the intervening years has equalled that of any other black preacher. He was born to Thomas and Elizabeth Charity Bowser, who lived in Hickman and Maury County, Tennessee. When Bowser was three years old his family moved to Nashville. His mother was a member of the Christian church, but Bowser at the age of fifteen joined the A. M.E. Bethel Church. At the age of twenty-one he was ordained a minister of the Methodist Church. He was educated in Nashville at Walden University. Bowser met Sam Davis, an ex-slave and a preacher in the Christian Church, who taught him the gospel and convinced him to give up his "denominational" Christianity. Bowser resisted what he called "being baptized again" since he had been baptized into the Methodist Church, but later he agreed for Sam Davis to baptize him according to the New Testament.23

Bowser pulled out of the Christian Church shortly after Campbell and Womack and joined hands with them in the work they had begun. With this modest beginning these three men were responsible for putting the restoration of New Testament Christianity among Blacks well on its way.

G. P. Bowser enjoyed a very wide acceptance within the restoration movement among Black people.24 Two reasons for this were that he was an excellent Bible scholar and preacher and that he pushed the idea of Christian education among Blacks until it became a reality. Therefore Bowser will be remembered for his evangelistic work and his work in Christian education.

As good a place as any to tell the story of Christian education among Blacks during this time is now. The story of Christian education among Blacks actually begins in the early days of this century when Aleck Campbell, S. W. Womack and G. P. Bowser organized a grade school in the Jackson Street Mission where the Bible was taught daily.25

One of the most exciting chapters in the Restoration of New Testament Christianity among Blacks has its beginning with these three men and a handful of disciples.

In 1905 Womack, Campbell, Bowser and others who were interested in starting a Christian school began to discuss the matter. Hope ran high, therefore, the possibility for such a school to begin were very good. Speeches were made to encourage the idea and money was collected. In October 1907 the school was opened. The enrollment was seventeen the first year. Bowser and Womack worked hard to construct a school in Nashville. The school did not remain in Nashville very long. In fact, it was moved to Silver Point, Tennessee in 1909. It was the general agreement that a smaller community would lessen the cost of maintaining the school. Silver Point seemed to be ideal for this purpose. Before a site was purchased a meeting was called to inform the people of that area of the intention to bring the school to that area. Bowser spoke at the meeting which was well attended. They were allowed by the county to use a one room school house until the new building was constructed. Therefore, a site was bought at the cost of $250.00 and a two story frame structure was erected at the cost of $600.00. Two teachers were employed, G. P. Bowser and the daughter of Womack, Philistia. Their salaries never were more than $50.00 a month .26

There are several other persons who were connected with the Silver Point School that should be mentioned here. Annie C. Tuggle, who was reared near Memphis, Tennessee, was greatly influenced by Aleck Campbell and Bowser. In 1913 Miss Tuggle became interested in the school enough to serve as an instructor and later as a solicitor. Then there was the daughter of Aleck Campbell, Alexine Campbell Page, who was also one of Bowser's teachers. T. H. Busby was a protege of Bowser at the Silver Point School. Busby was a student and served as a music teacher. He was an excellent song leader. In his youth Busby did not show much promise as a preacher, but in his later years he became a very popular and well known evangelist. He was holding meetings in mission points throughout America. T. H. Busby became a tower among the Black preachers.27

The year 1916 was the highest point in the school's history. A. M. Burton was sent by David Lipscomb to survey the future prospects of the school. He was accompanied by J. S. Hammond, who was also interested in the school. Burton's report showed that there were eight acres of poor land, Bowser's home, a frame Chapel building, and nine boarding students.

As a result of Burton's visit more property was purchased, a brick chapel was erected, the materials in the old chapel were used to build a house for girls, and the school was organized under a board of trustees composing Black and White members.

The Silver Point school was short lived in spite of the efforts put forth to keep it open. It faced two major problems from the beginning, students and finance. It gradually withered away. Its doors were closed at the end of the 1919-1920 school year.

A new school was planned for South Nashville to be opened in January of 1920. This school was called "Southern Practical Institute." It was born and died in less than two months. Bowser, assisted by Annie Tuggle and Willie Wall, started the school. Bowser was determined to have a Christian school among Blacks.

His next attempt to start a school was Detroit, Michigan, that operated a short while. He moved to Fort Smith, Arkansas where he operated the Bowser Christian Institute for eight years. From there he went to Fort Worth, Texas, where he organized another school.

Not any of his schools lasted very long. But Bowser preserved the idea of Christian education among Black people. The idea did not die when Bowser died in March of 1950. But his efforts were kept alive in the establishment of the Nashville Christian Institute and Southwestern Christian College in Terrell, Texas.

Before leaving G. P. Bowser and going on to Keeble, there are a few of the many preachers influenced by Bowser that must be mentioned here. The first of which is Alonzo Jones, who was converted by Bowser. Alonzo Jones left Mississippi and came to Tennessee where he started and sustained the work among Blacks in Chattanooga. He is said to have been one of the best preachers during the 1920's.28

I mention next in connection with Bowser his son-in-law, M. F. Holt. Holt was married to Bowser's daughter Thelma. He was born in 1895 in Marshall County, Tennessee. D. M. English baptized him in 1909. Holt was the first full time preacher for the Jefferson Street church in Nashville. Holt worked with five congregations at the same time during the 1940's.29

Then there was R. N. Hogan, who was born in 1902 in Hickman County, Tennessee later to live in Blackton, Arkansas. Bowser brought Hogan to Silver Point at the age of fourteen and kept him in his home for four years. Hogan traveled with Bowser on his engagements and learned to preach under Bowser's influence. Hogan at the age of seventeen had already baptized seventy people. He started about fifty new congregations and baptized over fifteen hundred people. R. N. Hogan for many years has lived in California and is one of the strongest influences for the cause of Christ today.30

The last of these preachers influenced by Bowser that I mention is George E. Steward, better known among the Black disciples as the "blind wonder." Steward was born in 1906, in Gail, Louisiana. Bowser baptized him in 1931. At the time Bowser met Steward he was preaching in a Baptist church. Steward was educated in the school for blind at Austin, Texas, therefore he could read. Bowser had very little difficulty in converting Steward and his wife. Since that time the two of them have done and is doing a world of good for Christ. Steward has become one of the most effective preachers in our times.31

We must now give our attention to the great wonder and a legend in his own times, the late and beloved Marshall Keeble. Keeble was born in 1878 in Rutherford County, Tennessee. He was baptized by Preston Taylor into the Gay Street Christian Church when he was fourteen years of age. Keeble never finished junior high school. One of the greatest influences in his life was his marriage to the daughter of S. W. Womack, Minnie Womack.

Keeble started preaching sometime after he left the Christian Church, along with Womack and Campbell, near the turn of the century. In 1908, Womack reported to the Advocate that Keeble had preached to a small group of disciples at Dozier School house. Keeble gave the credit for his preaching to Campbell, Womack and Bowser. These men encouraged him in many ways. They carried Keeble with them on their appointments and he was very active in the Jackson Street mission from the beginning. His mother-in-law never thought Marshall would make a preacher. Keeble told an experience that encouraged him to spend the rest of his life preaching. It was the first meeting that he ever conducted. The meeting took place at Center Star near Centerville, Tennessee. He baptized twenty-five in Blue Buck Pond.

Keeble was nearing the unique fame that would make him unequalled by any other preacher of Restoration History. The year was 1916 when he preached two nights in the home of a very prosperous Black farmer named Bose Crooms who lived near Henderson, Tennessee. The Crooms family were the only Black Christians around Henderson. The next year Keeble preached a four night stand in a rented Methodist building. After this Keeble was given an appointment for 1918 the year when the fabulous career of this man really began.

Bose Crooms went to N. B. Hardeman to arrange a meeting place for the 1918 meeting. A Baptist meetinghouse was secured only to learn later that the Baptists had gone back on their agreement when they learned that Keeble was coming to town. Hardeman then secured the Oak Grove school house for the meeting. The meeting started the third Sunday in July, 1918 and continued for three weeks. Eighty-four persons were baptized in that meeting. Keeble really stirred up the people around Jacks' Creek, Tennessee. Keeble moved into Henderson and started another church there.

Keeble's reputation as a gospel preacher was firmly built in the 1920's. He enjoyed a general recognition among the churches after his famed meetings in the State of Florida. He began to receive calls from all over the nation to come and preach. He participated in the Restoration of New Testament Christianity on an international basis, traveling for seventy years without discrimination as an active evangelist into every state of America and around the world. He established over 400 congregations and baptized 40,000 people.

FOOTNOTES

1 Alfred J. DeGroot and Winfred E. Garrison, The Disciple of Christ, St. Louis: The Bethany Press. 1948, p. 469.

2 J. E. Choate, Roll Jordan Roll, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co. 1968), p. 3.

3 Alfred T. DeGroot and Winfred E. Garrison, The Disciple of Christ, St. Louis: The Bethany Press. 1948, p. 471.

4 Alfred J. DeGroot and Winfred E. Garrison, The Disciple of Christ, St. Louis: The Bethany Press. 1948, pp. 468-469.

5 Ibid., p. 472.

6 Ibid., p. 472.

7Ibid., p. 472.

8 Alfred J. DeGroot and Winfred E. Garrison, The Disciple of Christ, St. Louis: The Bethany Press. 1948, pp. 470 & 474.

9 Ibid., p. 476.

10 Earl T. West, The Search for the Ancient Order, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co. 1964), pp. 329-330.

11 Ibid., p. 331.

12J. E. Choate, Roll Jordan Roll, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co. 1968), p. 4.

13 Ibid., p. 4.

14 B. C. Goodpasture, ed., Gospel Advocate, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co.), p. 739 & 1868.

15 B. C. Goodpasture, ed., Gospel Advocate, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co.), pp. 199 & 1868.

16 J. E. Choate, Roll Jordan Roll, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co. 1968), p. 1.

17 J. E. Choate, Roll Jordan Roll, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co. 1968), pp. 6-7.

18 Ibid., p. 5.

19 Ibid., p. 9.

20 Ibid., p. 3.

21 Ibid., p. 12.

22 Carl E. Gaines and John C. Whitley, Black Preachers of Today, Vol. 1, 1974.

23 J. E. Choate, Roll Jordan Roll, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co. 1968).

24 Ibid., p. x.

25 J. E. Choate, Roll Jordan Roll, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co. 1968), p. 23.

26 Ibid., pp. 24-25.

27 J. E. Choate, Roll Jordan Roll, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co. 1968). p. 85.

28 J. E. Choate, Roll Jordan Roll, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co. 1968), p. 85.

29 Ibid., p. 91.

30 J. E. Choate, Roll Jordan Roll, Nashville: (Gospel Advocate Co. 1968), p. 90.

31 Ibid., p. 91.

![]()

A Great Man Gone

On July 13, 1920, Brother S. W. Womack departed this life. He had been sick for nearly two years, and had been confined to his room about ten months. His suffering was great at times, but he never once murmured, but was cheerful all the time. I was absent when he died. I was in a meeting at Latham, Tenn., and they wired me three or four messages, but I failed to get either one until it was too late for me to attend the funeral. It had been my desire to be present at this good man's funeral. Old Brother Clay, who had labored with him for years, spoke over the remains; also Brother Dowell, a young brother who is a product of Jackson Street Church, spoke encouraging words. Brother F. W. Smith and Brother A. B. Lipscomb were present and spoke words of com for, and all who heard them were uplifted and edified. Brother A. M. Burton was also present. This Christian man never talks much in a public way, but his life tells what he is. These brethren were all interested in Brother Womack and his work, and during his life of over forty years in the ministry they greatly helped in supporting him in his work.

I have often heard Brother Womack say he had gone to places to preach where there was not a colored member of the church of Christ, and his own race would fail to aid or support him, and the white people would supply his needs; and I believe if there ever was a dollar safely invested, it was when given to this faithful preacher of the gospel.

I married in this family about twenty-five years ago, and I have been closely connected with him ever since, and I must say that I never heard him speak rashly or get angry. He seemed to keep a joyful spirit all the time. He has been a great help to me. He first got me to see that I was wrong while working with the "digressives," and I came out from them over twenty years ago, and from that time on I tried to make my life like his; and though he is gone, I shall continue to try and imitate the Christian life he has left behind.

Last September he was with me at Sugar Grove, Ky., where I was holding a meeting. He established this congregation and was highly esteemed by them all. While there he was very feeble, and told them that he would never meet them on earth any more, but to live so they could meet on the other side of Jordan.

His funeral was conducted at the Jackson Street church, where he worshiped when at home; and when he got so weak he had to walk with a stick, he would often preach to the congregation while sitting in a chair. He considered this congregation to be the cream of his labors; and although some time ago some trouble arose and caused division, he remained and endeavored to unit us again and stop the division, and we who remain are yet working and praying that unity may be brought about in the future. The Jackson Street Church never once neglected him in any way. They contributed regularly to him, and the members were always giving him something to comfort him in his sickness. Other churches would send donations to him often. The white brethren and sisters all over the South sent him comforting messages. Some of them would say they had never seen him, but they had read of his life in the Gospel Advocate.

It was Brother Womack's delight when he was in town to visit the Gospel Advocate office, because, he said, he was always made welcome by the whole staff. Whenever he got puzzled over any passage of scripture, he would always have a conference with old Brother David Lipscomb during his life time. After Brother Lipscomb died, he continued to go and talk with Brethren A. B. Lipscomb, J. C. McQuiddy, F. W. Smith, and others, and by this means he was always prepared to instruct his people. He always read his Bible daily.

Brother Womack leaves a faithful wife, two daughters, two grandchildren, and a host of relatives and friends to jour his departure. "Be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life." (Rev. 2:10.)

-Keeble, Marshall "A Great Man Gone" - Gospel Advocate July 29, 1920. pages 744-745, provided by Terry J. Gardner- 8.2012

![]()

A Eulogy of Samuel W. Womack, 1920

On July 13, 1920, Brother S. W. Womack departed this life. He had been sick for nearly two years, and had been confined to his room about ten months. His suffering was great at times, but he never once murmured, but was cheerful all the time. I was absent when he died. I was in a meeting in Latham, Tenn., and they wired me three or four messages, but I failed to get either one until it was too late for me to attend the funeral. It had been my desire to be present at this good man's funeral. Old Brother [Henry] Clay,10 who had labored with him for years, spoke over the remains; also Brother [Calvin] Dowell," a young brother who is a product of Jackson Street Church, spoke encouraging words. Brother F. W. Smith and Brother A. B. Lipscomb were present and spoke words of comfort and all who heard them were uplifted and edified. Brother A. M. Burton was also present. This Christian man never talks much in a public way, but his life tells what he is. These brethren were all interested in Brother Womack and his work, and during his life of over forty years in the ministry they greatly helped in supporting him in his work.

I have often heard Brother Womack say he had gone to places to preach where there was not a colored member of the church of Christ, and his own race would fail to aid or support him, and the white people would supply his needs; and I believe if there ever was a dollar safely invested, it was when given to this faithful preacher of the gospel of Jesus Christ.

I married in this family about twenty-five years ago, and I have been closely connected with him ever since, and I must say that I never heard him speak rashly or get angry. He seemed to keep a joyful spirit all the time. He has been a great help to me. He first got me to see that I was wrong while working with the "digressives," and I came out from them over twenty years ago, and from that [time] on I tried to make my life like his; and though he is gone, I shall continue to try and imitate the Christian life he has left behind.

Last September he was with me at Sugar Grove, Ky., where I was holding a meeting. He established this congregation and was highly esteemed by them all. While there he was very feeble, and told them that he would never meet them on earth any more, but to live so they could meet on the other side of Jordan. His funeral was conducted at the Jackson Street Church, where he worshiped when at home; and when he got so weak he had to walk with a stick, he would often preach to congregation while sitting in a chair. He considered this congregation to be the cream of his labors; and although some time ago some trouble arose and caused division, he remained and endeavored to unite us again and stop the division, and we who remain are yet working and praying that unity may be brought about in the future. The Jackson Street Church never once neglected him in any way. They contributed regularly to him, and the members were always giving him something to comfort him in his sickness. Other churches would send donations to him often. The white brethren and sisters all over the South sent him comforting messages. Some of them would say they had never seen him, but they had read of his life in the Gospel Advocate.

It was Brother Womack's delight when he was in town to visit the Gospel Advocate office, because, he said, he was always made welcome by the whole staff. Whenever he got puzzled over any passage of scripture, he would always have a conference with old Brother David Lipscomb during his life time. After Brother Lipscomb died, he continued to go and talk with Brethren A. B. Lipscomb, J. C. McQuiddy, F. W. Smith, and others, and by this means he was always prepared to instruct his people. He [Womack] always read his Bible daily....

-Robinson, Edward J., A Godsend To His People, Chapter 2, "If It Were Not For The White Christians: Keeble 1920," pages 15,16

![]()

Directions To The Grave of S. W. Womack

S. W. Womack is buried in the Greenwood Cemetery, Nashville, Tennessee, located at 1428 Elm Hill Pike. It is an African-American cemetery. It is located just down the road from the Gospel Advocate Bookstore. If heading west on I-40, take Exit 213, Spence Lane and turn right. Turn left on Elm Hill Pike, and entering the cemetery on your right. When you enter you will come to a roundabout. Head around to the back of the roundabout and continue toward the office. There will be a line of trees on your left as you pass the large section on your left. When you come to the last tree closest to the road, stop the car and go into your left, just next to the last tree. Go toward the center until you see section, searching for a marker named CARUTHERS: Womack/Jordon. This is the only marker to mark the Womack grave plot. Plot Info: Burial Date - July 16, 1920; Section 3, Lot 154 SW 1/4 Space/Grave 997 - His daughter, Minnie Keeble is in an unmarked grave, the location of which is: Burial Date - Dec. 13, 1932; Section 5, Lot 172 N 1/2; Space/Grave 667

GPS Location

36.145786,-86.724016

Plot Info: Burial Date - July 16, 1920;

Section 3, Lot 154 SW 1/4 Space/Grave 997

![]()

Eugene P. Caruthers

July 17, 1923

January 10, 1980

CARUTHERS

Womack - Jordon

![]()

Photos Taken May 21, 2012

Courtesy of Scott Harp

www.TheRestorationMovement.com

Web Editor's Note: The day I visited the grave of S. W. Womack, I had just begun a week's Restoration Research trip with my dear friend Tom L. Childers. We had been set to meet at Crieve Hall Church of Christ where I would leave my truck at around 10am. As I arrived early in Nashville, I had an opportunity to run over to Greenwood Cemetery to see if I could find the grave of S. W. Womack. The people in the office were very helpful, and the location was identified. Unfortunately, though th efamily plot was identified, the actual grave location of S. W. Womack was not easily discernable since he had no personal marker.

![]()